Many notable figures came out of President Lincoln’s White House. The United States was famously changed by Cabinet members such as Secretary of State William Seward and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. However, one unsung man held significant influence over the day-to-day actions of the White House and in communities around the District of Columbia: William Slade. Slade was Abraham Lincoln’s valet (personal assistant as we would refer to the role today) and the head of White House staff.

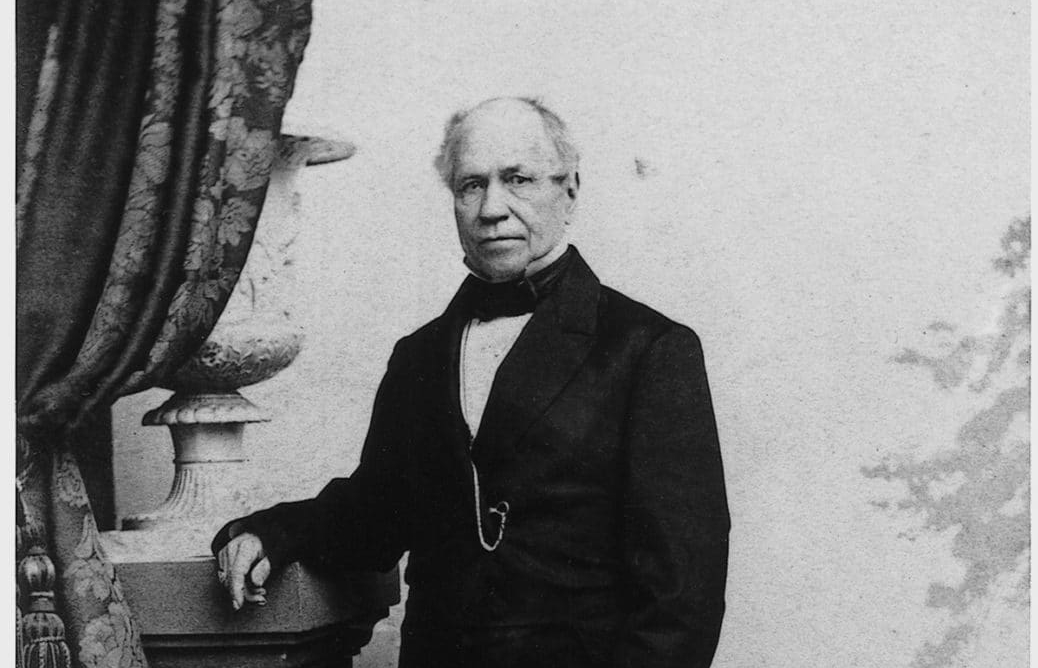

While many details of his early life are unrecorded, it is known that he was born of a free African-American family in Alexandria, Virginia in 1815.[1] He was described as being “medium height, olive in complexion, with light eyes and straight chestnut-brown hair.”[2] Slade’s lighter complexion may have afforded him opportunities when pursuing careers in northern Virginia and Washington due to the prejudices of the day. Later in his life in the 1850s, he worked as a porter in the Indian Queen Hotel in Washington, D.C., which allowed him to make connections with the politicians that frequented there. While working there, William Slade received the favor of Salmon P. Chase, the Secretary of the Treasury, which led him to his first role in government as a messenger for the Treasury Department in 1861.[3]

From there, William Slade became known for his service and personality. He was described as a great storyteller and whose wit “could make a horse laugh.”[4] These attributes caught the attention of Abraham Lincoln, who requested Slade be assigned the head of White House staff, as well as Lincoln’s personal valet. From this position, Slade formed a strong bond with Lincoln and his family. Slade’s oldest daughter, Katherine Slade (nicknamed “Nibbie”), recounted the times where she and younger brothers, Andrew and Jessie, played with Tad Lincoln, Abraham’s youngest son. These children were inseparable. Katherine recalled that Tad became unruly if he had not had the opportunity to play with the Slade children at their house on Massachusetts Avenue.[5]

Mr. Slade’s prominence in the Washington community went beyond his role in the White House. He was a member of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church and later founded the “Colored Presbyterian Church.”[6] Being a member of the spiritual community in Washington, Slade found prominence advancing the causes of African-American communities. He was the head of many groups for African-American progress including the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association (SCSA), which sought to track the growth of black businesses and the progress of education in black communities.[7] He also co-founded the Contraband Relief Society (CRS) in 1862 with Elizabeth Keckley, another member of the White House Staff that provided aid to “contrabands” across D.C.[8] In advance of the Emancipation Proclamation, William Slade presented President Lincoln with a petition to have African-Americans in charge of selecting the leaders of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) in 1862.[9]

William Slade passed away from complications from a “disease of the heart” on March 16th, 1868.[10] Friends and family remembered him reverently, and President Andrew Johnson gave a final farewell to the man who kept the White House going strong.[11] Slade left behind a small fortune of over $100,000 (around $2 million in 2021) and a vast legacy to be followed. One of his youngest sons, Andrew Slade, followed in his footsteps by becoming the first African-American Senate page in 1869.[12]

William Slade stood as a symbol of success and progress during his time in the White House and for generations to follow. The dedication he showed towards President Lincoln, his staff at the White House, and the African-American community of Washington enshrined him as a figure of respect. The actions that William Slade took in his daily life helped advance each community he had been a part of. William Slade is a wonderful example of a person dedication to progress and social justice, and deserves greater recognition for his important role in the American story.

[1] “William Slade (1815-1868),”Findagrave.com, January 17, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/221782985/william-slade

[2] John Washington, They Knew Lincoln, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 107.

[3] Senate Historical Office, “Andrew Slade: First African American Senate Page,” February 8, 2021

[4] Washington, They Knew Lincoln, 107

[5] Washington, They Knew Lincoln, 107-109.

[6] Alexandria Gazette, March 17, 1868.

[7] Natalie Sweet, “’A Representative of our people’: The Agency of William Slade, Leader in the African American Community and Usher to Abraham Lincoln,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association Vol. 34, Issue 2 (Summer 2013): 21-41.

[8] Senate Historical Office, “Andrew Slade: First African American Senate Page”

[9] Sweet, “The Agency of William Slade”

[10] The Evening Star, March 16, 1868.

[11] Virginia Free Press, March 26, 1868, 4.

[12] Senate Historical Office, “Andrew Slade: First African American Senate Page”