By Niles Anderegg

On the tour of the Cottage, visitors hear of Lincoln’s use of a parable of “the Wolf and the Sheep.” The point of recounting this story is to explore Lincoln’s views on the institution of slavery, and in particular how his attitude towards slavery and slaveholders had changed over time. But Lincoln’s story also tells us something about his employment of rhetoric, and especially his use of parable.

On the tour of the Cottage, visitors hear of Lincoln’s use of a parable of “the Wolf and the Sheep.” The point of recounting this story is to explore Lincoln’s views on the institution of slavery, and in particular how his attitude towards slavery and slaveholders had changed over time. But Lincoln’s story also tells us something about his employment of rhetoric, and especially his use of parable.

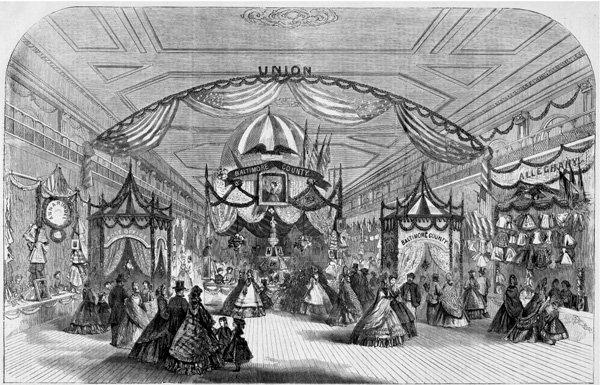

The Wolf and the Sheep story, which would have reminded Lincoln’s audience of the parable of the Good Shepherd from the Gospel of John, comes from a brief, little remembered speech Lincoln gave in Baltimore in April of 1864. The setting itself is important. Maryland, a border state that had remained in the union, was at this time considering a new constitution that would include a provision ending slavery. So Lincoln went to Baltimore to support and persuade Marylanders to adopt the new constitution. The speech marked a rare moment for Lincoln, who seldom left Washington (he lived at the Cottage during the summer months of the war in part because he believed that, as Commander-in-Chief, he needed to remain in the district and in communication with the War Office). The venue where Lincoln gave his speech was a sanitation fair, which was essentially a fundraiser for the United States Sanitary Commission and the work it did on behalf of wounded and sick soldiers.

The speech itself is interesting for several reasons. Lincoln begins by reminding his audience that much has changed since the war began and that the people of Baltimore, especially, had seen much of that change. He alludes to the difficulty Union soldiers had in marching through the city in 1861 when they were faced with riots. Now, three years later, the citizens of Baltimore are raising money and urging support for those same troops. Lincoln goes on to explain that Baltimore has not only changed its view of Union soldiers but has changed in its attitude towards slavery as well.

It is in this context of change that Lincoln uses the Wolf and the Sheep parable. He starts off by explaining that “the world has never had a good definition for the word liberty,” and that in the midst of the Civil War, America is in need of a good definition. He goes on to say that everyone talks about liberty but that when they use that word they don’t all mean the same thing. Lincoln’s remark is surprising: “liberty” is one of the defining words of American history. The revolutionary generation called themselves the Sons of Liberty, so they presumably had a definition for liberty. Jefferson talks about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness in the Declaration of Independence, so he too must have had a definition for liberty. But Lincoln says no: in America, and in the world, liberty means different things to different people.

Lincoln goes on to give us two basic definitions of liberty. He notes that “with some, the word liberty may mean for each man to do as he pleases with himself and the product of his labor” while with others liberty is where men are free to “do as they please with other men and the product of other men’s labor.” He goes on to point out that these two definitions are incompatible. He also points out that each believer in one definition of liberty will call the other definition tyranny. Then, instead of explaining which definition he believes is the correct one, he presents these two definitions in the form of a parable.

Lincoln dives into his parable almost without warning. “The shepherd,” he says, “drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as a liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act as the destroyer of liberty, especially as the sheep was a black one.” He goes on to explain that his policy of emancipation is viewed the same way as the sheep and the wolf view the shepherd, even in the North. But he makes clear that it is the sheep’s definition that he believes is the right one. He goes on to say that the people of Maryland were “doing something to define liberty” and that their work has meant that “the Wolf’s dictionary has been repudiated.”

The language of this parable represents an evolution in Lincoln’s thinking. He clearly defines the controversy over the meaning of liberty by creating a stark contrast which he applies directly to slavery. The wolf symbolizes those men who support a definition of liberty as: meaning to do as they please with other men and the product of other men’s labor. This is a strongly negative description for Lincoln, given that throughout his pre-presidency political career he went out of his way to not demean slaveholders in particular, and Southerners in general. Here, for example, is a passage from Lincoln’s debates with Douglas in 1858:

“Before proceeding, let me say I think I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation. If slavery did not now exist among them, they would not introduce it. If it did now exist amongst us, we should not instantly give it up. This I believe of the masses North and South. Doubtless there are individuals on both sides, who would not hold slaves under any circumstances; and others who would gladly introduce slavery anew, if it were out of existence. We know that some Southern men do free their slaves, go North, and become tiptop Abolitionists; while some Northern ones go South, and become most cruel slave-masters.”

The direct challenge to the morality of slaveholders found in the speech in Baltimore is a significant departure from Lincoln’s pre-presidency rhetoric, but it is entirely consistent with the theme of the speech, which is that of change. The Civil War changed the lives of many Americans, and it also changed Abraham Lincoln. He came to realize that in order to win the war and save the union he needed to end slavery. He reinforces this view at the end of the Baltimore address when he alludes to news reports of the massacre of “some three hundred colored soldiers and white officers” at Fort Pillow, reminding his audience that there were those who resisted the inclusion of African-American troops in the Union Army who were now calling for retribution on Confederate prisoners.

Lincoln’s remarks on the Fort Pillow massacre connects back to the “black sheep” he refers to in his parable. In Lincoln’s time (as well as in our own), the term “black sheep” had a negative connotation, describing a disreputable member of a family or group. Lincoln, however, turns this definition in a new direction. If the sheep is traditionally the victim of the wolf, how much more in danger is the black sheep, who stands out from the rest of the flock. In arming the former slave, Lincoln might not be able to save every one of those black sheep, but at least he was giving them a fighting chance against the wolf. In the gospel parable, we read: “And other sheep I have, which are not of this fold: them also I must bring, and they shall hear my voice; and there shall be one fold, and one shepherd.” Lincoln’s definition of liberty now included all Americans.

Click here to read the full speech.