By Dennis H. Cremin

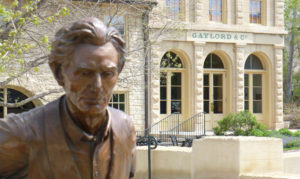

Historians use various lenses to view and focus in on the subject of their research. In the case of Abraham Lincoln, the lens varies depending on where you encounter him. At his home in Springfield, Illinois, the National Park Service uses the lens of domestic life to focus on Lincoln’s family, friends, and business associates. By comparison, a visit to the Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices provides insight into the life of a 19th century lawyer and his law associate. President Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, DC provides a “Home for Brave Ideas,” exploring ideas and concepts embedded in the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg address. President Lincoln’s Cottage is also linked to the Gaylord Building Historic Site in Lockport, Illinois in many ways. Both have relationships with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and Lincoln’s life runs through them both. They also connect visitors to their historic landscapes, and their historic structures provide a location to discuss complex ideas. The Gaylord Building was constructed in 1838 out of locally quarried limestone, and served as a storage depot for items needed to dig the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Today it is fronted by Lockport’s Lincoln Landing, which is marking its 10th anniversary. The interpretive park investigates Lincoln, the Illinois and Michigan Canal, and the Lockport community. The historical lens at this site is transportation, which was part of the 19th century political agenda of “internal improvements.” This political idea argued that the federal government should assist smaller communities in building an infrastructure to connect the communities and unite the nation.

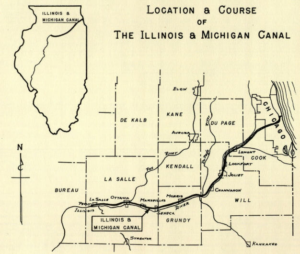

The theme of transportation as a lens for understanding United States History is exemplified in George Roger Taylor’s cornerstone work, The Transportation Revolution 1815- 1860. It provides great insight into how the nation that Lincoln grew up was knit together by turnpikes, canals, railroads, and river improvements. The book underlines how important it was to link urban communities to promote the movement of goods, people, and ideas in the antebellum United States. Geographically, Chicago is just about the furthest southwest point on the Great Lakes. It therefore served as a starting point to the West. Additionally, there is a small glacial moraine separating the waters of the Great Lakes which flows to the Atlantic through the St. Lawrence Seaway and from the Mississippi out to the Gulf of Mexico. A canal connecting these watersheds would connect New York, through the Hudson River, Erie Canal, and the Great Lakes, to New Orleans, by way of the Chicago River, the new 96-mile Illinois and Michigan Canal, the Illinois River, and the mighty Mississippi.

Abraham Lincoln learned from hard experience the importance of these internal improvements. As a young man, he watched crops and goods move slowly on dirt roads and rivers. When he was nineteen, Lincoln worked on a flatboat that moved goods on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Ultimately, he and some companions floated all the way down the Mississippi to New Orleans. In the Queen City, they sold all the goods and even sold the wood that the made up the raft itself before returning home via a steamboat. He made another flatboat trip to New Orleans in 1831. His experiences uniquely qualified him to consider the importance of a canal that could transport goods on waters routes that were too shallow or had too many rapids.

Lincoln supported the Illinois and Michigan Canal throughout his career. As a young congressman he was proud to announce the canal’s opening in 1848 on the floor of Congress, saying, “Take, for instance, the Illinois and Michigan canal… That canal was first opened for business last April. In a very few days we were all gratified to learn, among other things, that sugar had been carried from New Orleans through this canal to Buffalo in New York.”[1] The canal could move bulk commodities inexpensively, and they could then be distributed along the Erie Canal and beyond. In the inaugural year of the canal’s operation, Lincoln traveled on the waterway, and he may have made other trips along the canal. Local lore even holds that he dined at the Lockport home of William Gooding, the canal’s Chief Engineer.

Even during the Civil War, Lincoln turned his attention to internal improvements, including the Illinois and Michigan Canal. With the Confer dates controlling the Mississippi River early in the war, commerce along the Great Lakes was especially important. In 1862, Lincoln proposed improvements to the Canal to increase its size so that warships could travel between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. The United States Congress, however, did not support the proposal. Even after Lincoln’s death the association with the canal continued, when the funeral train carrying Lincoln’s remains rolled through Lockport along the site of Lincoln Landing. The power of place allows such a meaningful narrative to be woven.

The Gaylord Building and the adjacent Lincoln Landing provide unique insights into the concept of internal improvements that the Whig, and later, Republican Party, would champion in support of the federal government funding projects that linked the rapidly expanding United States. This expansion of the country during Lincoln’s lifetime was amazing, with nineteen states admitted to the union, including states as regionally diverse as Minnesota, Kansas, and California.

Standing on Lockport’s Lincoln Landing, visitors encounter the story of Lincoln, the canal, and the Lockport community. The core message is that Lincoln continually advocated for the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Lockport became the headquarters for the construction and administration for the canal that connects Chicago to La Salle, Illinois for waterborne commerce. It is a route that continues today with the Illinois Waterway.

Robert O. Carr developed Lincoln Landing. As a young man, he read Paul Simon’s book on Lincoln’s early legislative years that detailed Lincoln’s role in championing Lockport and the waterway while he was a state legislator. Over time, Carr’s vision grew to include a beautiful park that features a unique statue of Lincoln and interpretive medallions with information on people associated with the canal and the community.

Lincoln Landing and President Lincoln’s Cottage are further linked through November 2019, as scale models of the Lincoln in 3 Poses statue by artist David Ostro are on display at each site. Ostro’s life-size statue is a central focus of the Lincoln Landing interpretive park. On loan from Robert O. Carr’s Give Back Foundation and Lewis University, the scale models address the complexities surrounding time and space. As Ostro said, “I began to experiment with Lincoln in a number of shared poses and expressions with the hope that it would not only bring his personality to life, but also the heavy, frozen bronze as well. My goal with the piece was to balance traditional representation with contemporary thought.” Please consider visiting President Lincoln’s Cottage and the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Gaylord Building to see two of three existing scale models.

Dennis H. Cremin, Ph.D. is the Chair of the History Department at Lewis University. He served as the Director of Interpretation for Lockport’s Lincoln Landing.

[1] Roy P. Basler, ed. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 1:483.