By Callie Hawkins

On December 17, 1860, the South Carolina Legislature called for elections to a state convention to be held in Charleston. The result of this convention was the unanimous vote for secession on December 20, 1860. Secession, however, was not a new concept. In fact, both northern and southern states had threatened secession since the 1790s, though ultimately no action was ever taken.

The possibility that Republican Abraham Lincoln would be elected 16th president of the United States sent the South into a state of mass hysteria, and as one North Carolina congressman confirmed, “No other ‘over act’ can so imperatively demand resistance on our part as the simple election of their [Republican] candidate.”[1] By 1860, secession was accepted by the South as the best way to protect its rights and preserve its institutions from northern interference. Lincoln’s election set the wheels of southern secession in motion, though it’s likely that Lincoln himself questioned how far the threat of the southern states would go, stating, “The people of the South have too much sense to attempt the ruin of the government.”[2]

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina did secede from the Union stating the major reasons as matters of race, economics, and politics in “An Ordinance to dissolve the Union between the State of South Carolina and other States.” This action prompted ten other states to follow suit between December 1860 and May 1861 and propelled the United States toward civil war.

Source: James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 230-237.

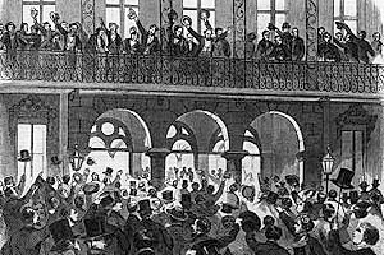

Image: South Carolina Convention, December 1860; Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division