The beginning of 2024 was an invigorating time for the team at President Lincoln’s Cottage, thanks in large part to our special exhibit, Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project, which opened January 5 and closed on February 19. The exhibit, for those of you who missed it, featured presidential portraiture and personal essays that commented on presidential incarceration records and spoke to the injustices of the justice system. We hosted the exhibit at the Cottage in partnership with the Justice Arts Coalition. The project was made possible by the generosity of the Justice Arts Fund.

“It was one of the most memorable projects I have been a part of at the Cottage,” said Sara Grace Grider, a Museum Program Associate (MPA) who was involved with installing and interpreting the exhibit. Sara Grace and the other MPAs were in close contact with incarcerated curators and artists throughout the process (see this article by fellow MPA Haley Bryant). During the exhibit run, the MPAs would end their regular guided tours with a discussion of the art, making the connection to Lincoln’s “unfinished work” of advancing freedom. “The experience changed my perspective. I didn’t know much about incarceration and prison reform before the exhibit, and I learned a lot. I think going into it I had subconscious assumptions, and talking with the incarcerated artists dispelled those notions and humanized them.”

Photo from the opening reception by Liza Harbison

The experience was life-changing for Caddell Kivett, called “Monty” by those who know him, the visionary behind the exhibit, who assembled the Committee on Incarcerated Artists and Writers (CIAW) to help curate the installation. “In a crazy way developing the exhibit made me feel more human. People treated me as another person working on a project… I so appreciate how the Lincoln’s Cottage team and the MPAs were willing to connect on a basic human level and act as proxies for the artists who could not attend in person,” he told me on a recorded phone call from Nash Correctional Institution where he is incarcerated.

The artists who participated in the exhibit were similarly impacted. Dolores Harrison, whose father Bryant Harrison wrote a beautiful piece for the exhibit that you can read here, spoke of how excited her father was to be selected, and, on a deeper level, to be heard. The experience brought her closer to her father, who has been incarcerated since she was five because he shared with her early drafts of his work. “The experience has really has given me a different insight into his life, emotions, and experiences— something you can’t get from a monitored fifteen-minute phone call.”

Doloros was thrilled to see her father’s work in an acclaimed exhibit– one which was featured by NPR, the Charlotte Observer, WTOP, Fox 5 News, and other publications. “It was exciting to see his work in the Cottage. His piece really brought the whole exhibit together, and made me proud,” she said.

Excerpt from America by Bryant Harrison. Read the full piece here.

Though it had been an early selection by the CIAW, her father’s piece was almost omitted from the exhibit because of an oversight stemming from the complexities of curating an exhibit remotely, highlighting how easy it is for voices to be silenced even as we work to amplify them.

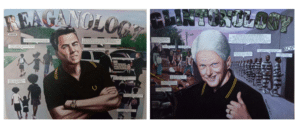

Likewise one of the star visual pieces of the exhibit, From School to Prison Pipeline: A Profound Impact on People of Color by Harry Ellis, never made it to the exhibit. There were difficulties and delays getting the artwork out of prison and to the Cottage. “This was one of my favorite pieces in the exhibit, and its absence illustrated the challenges that prisoners have engaging with the outside world,” said Sara Grace. “We had a printed reproduction, so visitors could get a sense of what the works look like, but we missed the originals.”

From School to Prison Pipeline: A Profound Impact on People of Color by Harry Ellis

In addition to commenting on the prison system, the exhibit included a call to reimagine it. Thus it was fitting to close the exhibit with a screening of the award-winning documentary, The First Step, about Van Jones’ successful efforts to work across the aisle to pass The First Step Act. “The content of the documentary pared well with what we were doing in the exhibit. It’s an example of how difficult it is to make meaningful legislative change…but that it is possible,” Monty (who was only able to see transcripts of the movie because of prison regulations) remarked.

Photo of The First Step screening by Bruce Guthrie

After the screening, filmmaker Lance Kramer, Monty, and Conor Broderick, a formerly incarcerated artist who helped to install the exhibit, participated in a panel discussion. Monty participated in the panel by calling in from Nash Correctional, as he did for the opening reception. Monty described the experience: “You know, it’s difficult to read a room alone in your 6×9 foot cell. I was worried that people couldn’t hear me—it’s an appropriate metaphor for the anxiety of being silenced in prison.” He was not able to hear the excitement when an audience member and artist named Carlos Walker stood up and said he was released from prison by the First Step Act, and how meaningful it was to watch see the actions that made his freedom possible by watching this terrific film.

Monty participating in a panel via amplified cell phone by Liza Harbison

Conor Broderick, Lance Kramer, and Carlos Walker

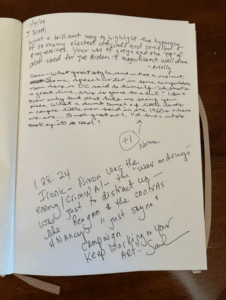

The difficulties in speaking out from prison, only make the messages of Prison Reimagined more important. Our hundreds of visitors who came through the exhibit were wonderfully receptive to these messages and had the opportunity to engage directly with the artists by sharing their thoughts and reflections on the writing and artwork in notebooks throughout the various rooms.

An example of visitor notes for the artists.

Sara Grace explained, “Visitors were really engaged. It lead to great conversations. I learned a lot working on the exhibit and talking with the artists but also through conversations with the public.”

Photo by Bruce Guthrie

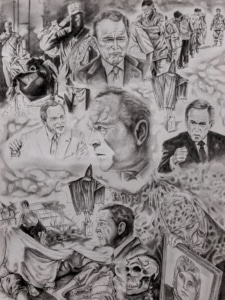

Sara Grace shared how artist Mike Tran, who painted 1 Strike, 2 Missed Opportunities, and 1 Lost Soul, reminded her that the most important takeaway should be to see the human behind the artwork. “Get to know us. We are human,” he implored. She believes the exhibit has been a reminder of that fact. “I think the exhibit helped people to look at the artists with more respect, and for that I’m proud and happy,” she said.

1 Strike, 2 Missed Opportunities, and 1 Lost Soul by Mike Tran

Doloros reiterated this sentiment: “Incarcerated persons are persons. Many struggle with mental health issues. Many need help. Many are not able to communicate emotions or fears. It’s important not to overlook that.”

And so it seems that everyone agreed that the success of the exhibit lay in the way it communicated the humanity of the artists— to the Cottage staff, to the artists themselves, and finally to the public.

Monty and the Justice Arts Coalition are looking for new venues for the exhibit, especially leading up to the election. “It has been a great way to push our message forward. We want to get as many eyes on it as possible,” Monty said.

We will keep our followers updated as to the next incarnation of this transformational exhibit. Stay tuned!

Photo by Liza Harbison

Rebecca Kilborne is the Marketing & Communications Manager at President Lincoln’s Cottage.