By Rae Katherine Eighmey and Erin Mast

Along with their two youngest sons, Willie and Tad, Abraham and Mary Lincoln brought their Midwestern values, habits of charity, and penchant for personal interaction to Washington. The war-challenged city would benefit. In 1862, just over a year after Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, reporter Noah Brooks wrote that there were “a little more than twenty hospitals in churches, the public halls of the Patent House and other public buildings.” Mary Lincoln was known to send food and treats to these hospitals, frequently “re-gifting” items that had arrived in the White House such as citrus fruits. Perhaps not to be outdone in charity work, later in the war Tad launched his own efforts to raise funds for the US Sanitary Commission. When his first efforts were quashed, he set up a stand in the White House lobby, selling beef jerky and fruit to the long lines of people waiting to see his father.[1]

These anecdotes are just two examples of the way food provides a delightful lens into the lives of Abraham and Mary Lincoln. What foods they purchased and from whom, what foods they enjoyed and in what company, and how they shared or gave food to others illustrates who they were as private citizens, how they felt about people around them, and how they viewed their role as the Presidential family during the great tragedy and upheaval of the U.S. Civil War.

From dishes Mary prepared and foods Lincoln enjoyed and shared with others throughout their lives, we have glimpses of their affection for one another, their relationships with people in the community, and the unique demands on, and conflicting expectations of, a President and First Lady to entertain in the midst of war.

In two companion articles, we will explore Abraham and Mary Lincoln’s connection to food, beginning with their very different circumstances in life — Abraham Lincoln raised on the frontier, in a family of relatively scarce means, and Mary by contrast, in a wealthy family in Lexington, KY.

In the first article, we turn our attention to Mary Lincoln.

Mary had grown up in Lexington in a wealthy, politically connected, slave-holding family. The closest she came to the kitchen was when she claimed in a letter that she was driving the cook to distraction. After marriage, however, she devoted herself to her husband and family. She became an accomplished cook, learning from the most popular cookbooks of the day, including a leading one written by Philadelphian Miss Eliza Leslie.

Prior to their marriage, Mary Lincoln had the advantage of her older sister’s kitchen in Springfield. Elizabeth Todd Edwards was accomplished in the kitchen and could make fancy foods as well simple foods. The girls’ mother had died when Mary was only six. Her father remarried and had nine more children with his second wife, eight of whom survived infancy. Mary grew up opinionated, educated (at a French-speaking boarding school), and politically aware. When Elizabeth married Ninian Edwards, the son of the Illinois governor, Mary visited and then moved to Springfield, taking some of the family’s fancy recipes with her, including an almond “courting cake.” Mary did not lack suitors when she arrived in Springfield, but it was Abraham Lincoln, whom she met at her sister’s home, who captured her attention. They shared a love of reading and politics — and a mutual respect for Henry Clay, Lincoln’s idol and family friend of the Todds.[2]

Abraham and Mary Lincoln could not have been raised more differently, and yet in spite of the vast differences between them in formal education, wealth, and social graces, they complemented each other. Mary’s abilities and connections were essential to Lincoln’s success.

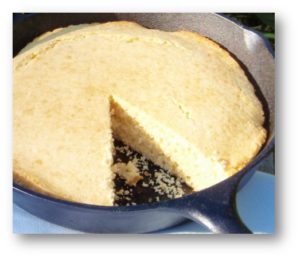

At first, Mary cooked family meals in their house’s open hearth, a cooking technology that took some time to master. This first Springfield kitchen would have been more familiar to Abraham Lincoln and what he had experienced throughout his youth and young adult years.. The open fireplace with pots hanging on cranes and Dutch ovens standing on their legs among the ashes was essentially the center of the home. Mary perfected making his favorite foods, especially cornbread and corn cakes which he said he could eat as fast as two women could make them.

In 1849, following Abraham Lincoln’s term in Congress, the Lincolns returned to their home in Springfield and began remodeling. Their home at the corner of Eighth and Jackson started out as a small cottage. By the time of the 1860 presidential election the house had been remodeled three times so that it was two stories with large pantry and a rear attached kitchen, equipped for sophisticated food preparation.

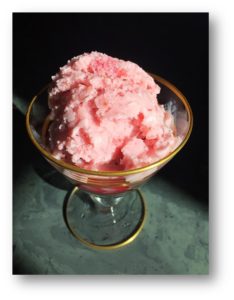

Mary was a masterful hostess during the ten years between the end of Abraham’s congressional term and his presidential election. They threw dinners, evening entertainments, even strawberry parties where it appears Mary served ice cream made from the bounty of seasonal fruits. Politicians, judges, and various guests from around the country praised her meals and were charmed by her company. The two were a power couple. And the few notes of invitation and diary entries that survive suggest that key connections were made and fostered in no small part due to her hospitality.

The Lincolns’ kitchen in Springfield had a modern free-standing stove. On June 9, 1860, the Lincolns purchased the Royal Oak #9 to replace an earlier model. This technologic wonder had a versatile oven that could be easily regulated with a small fire. Mary enjoyed cooking meals and treats for the Lincoln sons on it so much that it is said that she wanted to take it to Washington. But they left it behind along with their beloved dog Fido and Lincoln’s horse, Old Bob.

When the family and guests arrived in Washington ten days before the inauguration, they stayed at the fashionable Willard’s Hotel. On March 3, the new president held an inaugural dinner for his incoming cabinet of mock turtle soup, corned beef and cabbage, parsley potatoes, and blackberry pie.

The following day, March 4, the family and their guests arrived at the White House after the inauguration, parade, and reception. There they sat down to the “elegant meal” arranged for them by Harriet Lane, President Buchannan’s niece and official hostess. We don’t know the menu, but we do know that Mary Lincoln realized that she would no longer need to worry about cooking. She wrote to a long-time friend that “they have everything here. All you have to do is ask for it.” There were stewards, staff, and, a cook. We know the names of several cooks who worked at the White House, President Lincoln’s Cottage, or both: Cornelia Mitchell, Alice Johnstone, and Mary Williams. Stories from a collection of White House staff reminiscences published much later, suggest that Mary Lincoln did go down to the kitchen herself. She may even have put on an apron and cooked. But certainly, as one person said: “she knew how to choose meats, prepare vegetables, bake bread and that the steward, cook, and waiters knew that she knew.”

The White House calendar was filled with expectations. Mary Lincoln was experienced in organizing and hosting sophisticated and politically useful receptions in Springfield. Now in the White House simple home suppers gave way to formal and state dinners and parties with music and dancing. She filled the tables with French-style cuisine and decorated with beautiful fresh flowers from the conservatory and green house on the grounds. White House tradition also held that when Congress was in session the White House was to hold open house levees on both Tuesday evenings and Saturday afternoons. Throngs attended these food-less receptions.

Mary Lincoln decided to make a change. On February 5, 1862, after they had been in the White House for nearly a year, after forty major battles, minor skirmishes, and military engagements including Union defeats at Fort Sumter, and First Bull Run in July, Mary Lincoln turned White House social traditions upside down. She sent out 500 invitations to a gala event. The Marine band would play and a New York society catering firm would oversee the preparation of the sumptuous midnight supper including oysters, pate de foie gras, turkeys, partridges and quail, beef, charlotte russe, bon bons and fancy cakes. The tables were decorated with fanciful centerpieces – confectionary constructions of a ship under sail, a Chinese pagoda, and other exotic sculptures. Pyramids of fruit, cakes, and candies were said to be “delicately conceived and exquisitely executed.”

While the gayety continued well past midnight, upstairs there was little sleep as well. Willie Lincoln had come down with a fever in the days before the event. He was so ill, that Mary wanted to cancel the party. But the invitations had gone out. The doctor said he was on the mend, so they went ahead as planned. Willie lived through the night nursed by his parents who slipped away to check on him regularly along with other household staff.

In the days that followed Tad became ill, Willie got worse and died fifteen days later on February 20. His death is believed to have been caused by typhoid fever from tainted drinking water. Mary was inconsolable. She told the Taft boys, playmates of Willie and Tad, not to come anymore, their presence a painful reminder of Willie’s death.

A change of scenery in the summer of 1862 helped. In the middle of June, the Lincoln family packed up and, like many other families who had the means do to so, left the low-lying, marshy areas of downtown Washington, DC for healthier climates. Their move was relatively short. They relocated to a cottage at the Soldiers’ Home, only three miles north of the White House, but also 300 feet above sea level. Mary Lincoln was effusive about her appreciation for their new residence, writing to a friend, “In the loss of our idolized boy, we naturally suffered such intense grief, that a removal from the scene of our misery was found to be very necessary. We are truly delighted with this retreat, the drives and walks around here are delightful.”

However, with each passing year, Mary began to take more and longer trips away from Washington, where her husband was tied up entirely in the war effort. For example, with each passing hot season that the Lincolns lived at Soldiers’ Home (roughly June-November of 1862, ’63, and ’64), Mary’s trips north — to purchase furnishings to spruce up the Cottage as she had to do with the White House upon arrival, to vacation at resorts in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, to visit their eldest son Robert at Harvard — meant Lincoln was increasingly spending time at the Cottage without his immediate family.

On April 13, 1865, Lincoln visited Soldiers’ Home for the last time. Abraham and Mary looked forward to what they anticipated would be a very different season. They had no way of knowing how wrong they were, after the events of the next night fundamentally altered the nation forever. Mary’s grieving process was lengthy and well-documented, as was the grief of the nation.

Walt Whitman, who wrote an essay detailing his daily observations of the president as he passed the poet’s home on his commute from the Cottage to the White House, wrote of the impact of Lincoln’s death that April and beyond.

When lilacs last in the door-yard bloom’d

And the great star early droop’d in the western sky in the night,

I mourn’d—and yet shall mourn with ever-returning spring.

Four years and two months after he took the oath of office, President Lincoln’s remains were returned to Illinois. Mary Lincoln was too distraught to make the trip. She returned to Illinois in late May. Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train retraced the ten-day inaugural journey, and countless Americans mourned his death along the route. An interesting result of the country’s need to mourn is the rise of recipes in his honor, such as the “Lincoln Cake” a name given to several different recipes that emerged in the aftermath of his assassination. The cake is a fitting tribute to a man who was many things to many people, and whose legacy, like recipes passed down through generations, continues to evolve.

For a Lincoln Cake recipe click here.

Recipes and content adapted from Abraham Lincoln in the Kitchen: A Culinary Look at his Live and Times. Copyright Rae Katherine Eighmey, 2018, courtesy of Smithsonian Books.

[1] Accessed 2017.03.09 http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-history-of-pardoning-turkeys-began-with-tad-lincoln-141137570/#va4UVxEMARuZsAeD.99

[2] Accessed 2017.03.09 https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/liho/printVersion.html