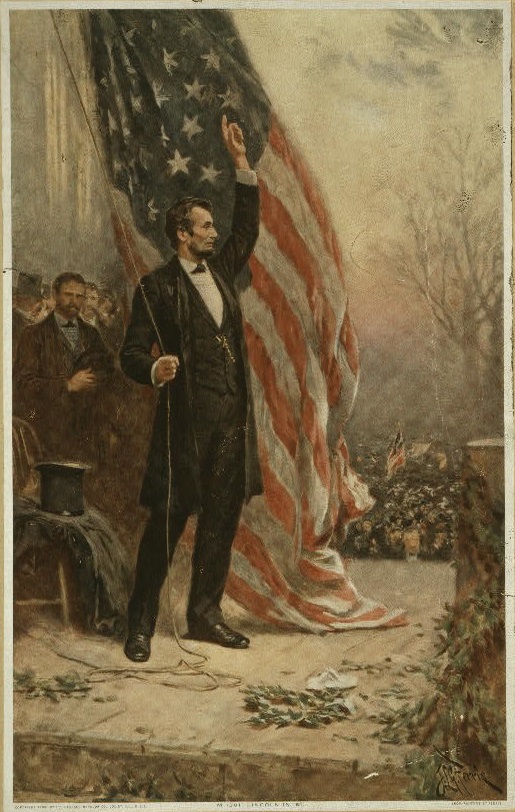

Abraham Lincoln raising a flag at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, in honor of the admission of Kansas to the Union on Washington’s Birthday, February 22, 1861. Library of Congress

By Zachary Klitzman

Let’s face it: Flag Day — which commemorates the official adoption of the Stars and Stripes by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1777 — is not the most widely celebrated holiday in America. An informal survey of the staff calendars at President Lincoln’s Cottage revealed that only 50% of the calendars listed the “holiday” (Father’s Day, Hallmark would be happy to know, appeared on all six calendars). In fact, in a 1998 survey, only 27 percent of Americans who participated said they knew when Flag Day is and what it means, whereas 18 percent were unaware of both the meaning and timing of the holiday. (The majority of those polled could name either the date or the meaning of the celebration, but not both.)

The holiday first came to national prominence when 19-year old Wisconsin school teacher Bernard J. Cigrand had his kids celebrate the “flag’s birthday” on June 14, 1885 by writing essays on what the flag meant to them. In subsequent years he traveled around the country promoting a June 14th Flag Day. On May 30, 1916, Cigrand’s dream became officially recognized, as President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation calling for a nationwide observance of Flag Day June 14th. Subsequently, in 1949 President Truman signed an Act of Congress designating the 14th day of June every year as National Flag Day. (Despite the legislation, Flag Day is not an officially observed U.S. Federal Holiday, and only one state, Pennsylvania, celebrates it as an official State Holiday.)

Though the holiday commemorates an event that took place during the War of Independence, the Civil War played a role in the history of the Flag. Nearly 30 years before Cigrand celebrated the flag’s birthday, Hartford, Connecticut observed Flag Day on June 14, 1861, using the commemoration to pray for the Union army and its goal of saving the country. However, the holiday did not catch on elsewhere in the country nor was it celebrated again in Hartford in subsequent years.

Lincoln himself never celebrated the holiday. Yet he made a very important decision in the Flag’s history as President. As he journeyed to Washington, D.C. for his 1861 inauguration, Lincoln spoke at Independence Hall in Philadelphia on February 22. Inside the historical building, Lincoln talked about how he was determined to uphold the legacy of the Founders and the Declaration, saying “all the political sentiments I entertain have been drawn … from the sentiments which originated, and were given to the world from this hall in which we stand.” He even went so far as to say that if he could not save the Union while adhering to the principles of the Declaration, “I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender” the document.

After giving his patriotic speech, Lincoln participated in a flag-raising ceremony outside the building to honor Kansas’ recent admission to the Union on January 29, 1861. Giving brief remarks before raising the new 34-starred flag (see image), Lincoln started by mentioning that though the flag the Founders originally raised at Independence Hall “had but 13 stars,” “each additional star added to that flag has given additional prosperity and happiness to this country.” Therefore, “cultivating the spirit that animated our fathers, who gave renown and celebrity to this Hall, cherishing that fraternal feeling which has so long characterized us as a nation … I think we may promise ourselves that not only the new star placed upon that flag shall be permitted to remain there to our permanent prosperity for years to come, but additional ones shall from time to time be placed there.” In these few words, Lincoln stated his policy that despite Southern states succeeding from the Union, their symbolic representation on the Flag of the United States would not be removed. Instead, they would continue to adorn the national symbol of unity.