Editor’s Note: The current attention on Supreme Court appointments in the final year of a President’s term calls to mind 1864, when President Lincoln was faced with that very issue. This excerpt of Michael Kahn’s article “Abraham Lincoln’s Appointments to the Supreme Court: A Master Politician at his Craft” examines how Lincoln addressed the subject. First appearing in the Journal of Supreme Court History 1997, Vol. II, this excerpt has been republished with the permission of the author.

Lincoln Names a Chief Justice

by Michael Kahn

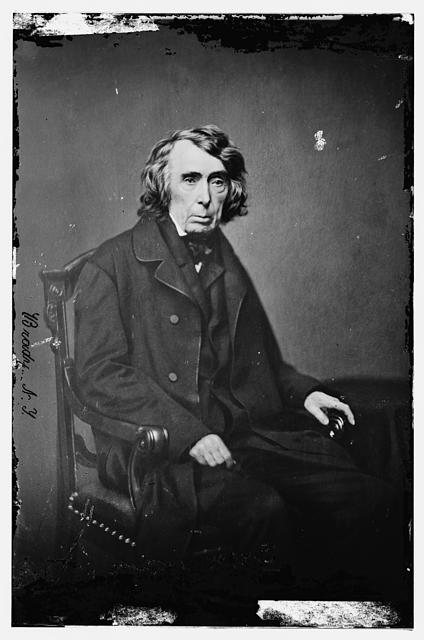

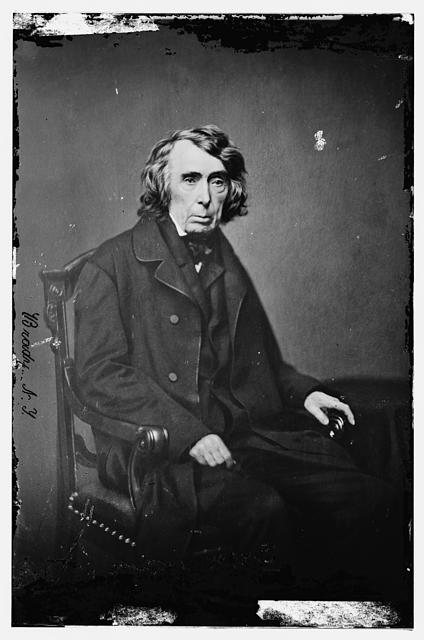

Roger Taney in 1855 (courtesy of the Library of Congress)

On October 12, 1864, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney died. [Abraham] Lincoln believed that in naming Taney’s successor he was making a choice that would have profound practical and political consequences for his second term. Lincoln also realized that the naming of the country’s fifth Chief Justice was a momentous historical event as the new Chief would continue the powerful role established by John Marshall and Taney.

Taney had been sick almost continuously since Lincoln’s first inauguration.[16] As a consequence, Lincoln and others had thought frequently about replacing him. Nevertheless, when the news of Taney’s death reached Lincoln, the President was deeply involved in both the military effort to win the war and his political effort to win re-election. Taney’s death instantly energized campaigns for several aspirants for the job including William M. Evarts of New York, Justice [Noah] Swayne of Ohio, Montgomery Blair of Maryland[17] and, ex-Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase.[18] Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay, recorded in his diary ”Last night Chief Justice Taney went home to his fathers … Already (before his old clay is cold) they are beginning to canvass vigorously for his successor. Chase men say the place is promised to their magnifico.”[19] Once again, Lincoln was inundated with advice that he immediately appoint each one: of these men and many others including Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton[20] and Attorney General Edward Bates (who asked the President for the appointment ”as the crowning retiring honor of my life” by letter of October 13, 1864).[21]

As ever, Lincoln was the shrewd politician and in October of 1864 he saw no profit in alienating any of the factions of his political support by making a selection before the election. There is no evidence that he seriously considered announcing his choice before he was re-elected.

Lincoln was not, however above using the enticement of the office to encourage campaigning on his behalf. The highest prize in that regard was the active political support of Salmon P. Chase, the former Senator, Governor, Secretary of the Treasury, and presidential candidate and a towering figure in the country. In the apt analysis of historian David Donald, after Taney’s death in October 1864 Chase took the “cue” and stumped for Lincoln throughout the Midwest in marked contrast to his earlier maneuverings in 1864 to replace Lincoln as President.[22] (Of course, Chase’s unusual behavior did not go unnoticed and rumors of a bargain surfaced.)[23]

Lincoln was re-elected on November 8, 1864. Congress and the Supreme Court were set to reconvene during the first week in December. The conflicting pressures on Lincoln regarding the appointment intensified directly after the election. Lincoln was variously urged by his friends and supporters to immediately appoint Chase; to forthwith appoint someone else (Evarts or Stanton or Swayne in particular); and, to never appoint the disloyal, overambitious, scoundrel Chase. Meanwhile, during the first months after his election Lincoln filled out his second term Cabinet and supervised the war effort.[24]

Then, with startling suddenness, Lincoln sent Chase’s name to the Senate on December 6, 1864. Lincoln did so with no advance notice. Even his closest advisors were uninformed before Lincoln put pen to paper and wrote, ”I nominate Salmon P. Chase of Ohio to be chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, vice Roger B. Taney, deceased.”[25]

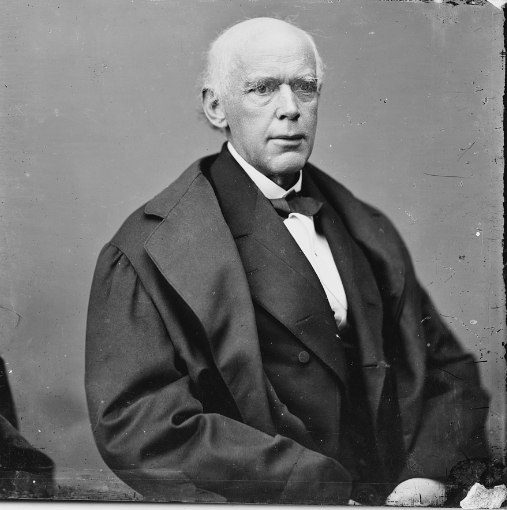

Salmon Chase (courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Lincoln’s decision to appoint Chase was a highly personal one.[26] Managing Chase in the Cabinet had occupied Lincoln’s mind almost continuously from Lincoln’s controversial decision to name his political rival to the position of Secretary of the Treasury in 1861 until Lincoln finally accepted his resignation from the Cabinet (Chase’s third such grandstand ploy) in the summer of 1864.[27] Because Chase was so obvious in expressing and pursuing his naked ambition and exhibited an imperious and arrogant style, Lincoln did not like Chase. But, Lincoln recognized that Chase was enormously talented and had a significant following among many politicians and certain segments of the public who found Chase’s style and substance more attractive than Lincoln’s. Moreover, the President believed, correctly, that on critical, fundamental articles of Lincoln’s political faith—abomination of slavery and the righteousness of the war effort—Chase was Lincoln’s true ally. So Lincoln, from the time of his first election, adopted the strategy of attempting to harness and co-opt Chase’s political and personal power to use in his own causes.

This strategy worked well enough until December 1864 as Lincoln manipulated Chase into serving his purposes in the Cabinet and in the re-election campaign. However, Lincoln had paid a heavy personal price for this strategy, both in terms of conflict within the Cabinet and in his seemingly endless dealings with a man who he believed to be petty and selfish. Now Lincoln was faced with the ultimate question of what to do with Chase. True to his character and style, Lincoln allowed others to express their opinions on the subject, but he made his decision alone without following any process or procedure.

Chase did everything in his power to force Lincoln’s hand. He unequivocally expressed a desire for the job[28] and he activated a political campaign for his appointment. He lobbied critical members of Lincoln’s coalition, such as Senator Charles Sumner, who intensely pressured Lincoln on Chase’s behalf.[29]

Through his friend Schuyler Colfax, Chase also addressed Lincoln’s chief reservation about him—that Chase would use the Bench as a platform to continue running for President—by promising to retire such ambitions.[30] Finally, Chase publicly paid political homage to Lincoln by actively campaigning for Lincoln’s reelection.[31]

Nevertheless, Lincoln was not forced to nominate Chase. Had he selected Evarts, Swayne, Stanton, or a dark horse candidate such as his friend Justice [David] Davis. Lincoln probably would have secured an easy confirmation process. The Supreme Court retired on December 5, 1864, for want of a quorum[32] so there was pressure to confirm any viable candidate. However, for Lincoln to choose someone other than Chase would have signified a failure to keep his apparent political bargain with Chase, the most prominent and politically powerful candidate for the job.

Lincoln justified his selection of Chase (to Representative George S. BoutwelI of Massachusetts) on two basic grounds that have become accepted dogma: (1) Chase was politically prominent and had a large political following and (2) Chase’s views were known to be in line with Lincoln’s on issues that were critical to the administration and would soon be decided by the Court, notably the upholding of Lincoln’s policies on emancipation and legal tender.[33]

There were, however, others—particularly Evarts—who could have filled those requirements. Moreover, selecting Evarts, Swayne, or Davis[34] for what was arguably the highest honor within the power of Lincoln’s presidency certainly would have been more personally satisfying to Lincoln. Ultimately, however, he selected Chase using the same criteria he used in selecting his other four nominees [to the Supreme Court].

In December 1864 Lincoln looked beyond the war and saw a troubled time during which the radicals in the Senate would need to be pacified and the courts would need to cooperate in the healing efforts. The choice of Chase as Chief Justice was far and away the best way—in Lincoln’s mind—of mollifying and co-opting the radicals,[35] of neutralizing (or at least silencing) Chase himself, a potentially dangerous and rancorous political enemy, and of providing leadership within the judiciary to promote administration efforts to preserve the Union in war and peace. The selection of Chase advanced every political and ideological goal that Lincoln was pursuing in December 1864. Therefore, Lincoln swallowed his personal qualms about Chase[36] and allowed his arrogant and obstinate rival the glory that he craved.

Once again, Lincoln was proven (at least during his lifetime)[37] correct. Chase’s nomination was unanimously confirmed on the day it was received[38] and lavishly praised in the press. On December 15, 1864, Chase was installed as Chief Justice. On February 1, 1865, the first African-American, John S. Rock, was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court on a motion by Senator Sumner that Chase insured was favorably received. The Taney era and the nightmare of Dred Scott were seemingly over.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Kahn is the author of numerous articles and three books relating to the history of politics and political cartoons and frequently lectures and teaches on these subjects. He is also an attorney, businessman, and charitable and private company board member. Mr. Kahn has also held numerous governmental appointments including serving as a chair on the California ISO Board of Governors, the California Green Team, California Electricity Oversight Board, and the California State Commission on Judicial Performance. Mr. Kahn received a BA from UCLA and a JD and an MA in political science from Stanford University where he was also a PhD candidate.

Mr. Kahn is President of the Board of Directors for President Lincoln’s Cottage.

NOTES

[16] Senator Benjamin Wade ironically noted “No man ever prayed as hard as I did that Taney might outlive James Buchanan’s term and now I’m afraid I have overdone it,” See J. G. Randall and Richard N. Current, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1955), at 270.

[17] Ibid at 272.

[18] Charles Fairman, The Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States: Reconstruction and Reunion 1864-88, Part I, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1971), at 8.

[19] Quoted in Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: a Biography, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952), at 491.

[20] Charles Fairman, The Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States: Reconstruction and Reunion 1864-88, Part I, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1971), at 9.

[21] Marvin R. Caln, Lincoln’s Attorney General Edward Bates of Missouri (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1965), at 311.

[22] David H. Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), at 536.

[23] J. G. Randall and Richard N. Current, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1955), at 271.

[24] Ibid at 265.

[25] Ibid at 273. David M. Silver, Lincoln’s Supreme Court (Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 1956), at 203.

[26] See generally Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: the War Years, vol. 3 (New York: Harcourt, Brace

& World, 1939), at 587; Charles Fairman, The Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States: Reconstruction and Reunion 1864-88, Part I, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1971).

[27] David H. Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), at 508.

[28] David M. Silver, Lincoln’s Supreme Court (Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 1956), at 200.

[29] Charles Fairman, The Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States: Reconstruction and Reunion 1864-88, Part I, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1971), at 6.

[30] David M. Silver, Lincoln’s Supreme Court (Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 1956), at 203.

[31] Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics (Kent, OH: The Kent University Press, 1987), at 241.

[32] David M. Silver, Lincoln’s Supreme Court (Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 1956), at 203.

[33] J. G. Randall and Richard N. Current, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1955), at 283. David H. Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), at 552. J. G. Holland, The Life of Abraham Lincoln (Springfield, MA; Gurdon Bill, 1866), at 497. Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Toward None: The Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), at 402.

[34] Lincoln remained close to Davis until his death and thereafter Davis administered his estate. See B. Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: a Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952), 450-511.

[35] David H. Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), at 552. J. G. Randall and Richard N. Current, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1955), at 274.

[36] Legend has it that Lincoln stated that he would “rather have swallowed his buckhorn chair than to have nominated Chase.” See J. G. Randall and Richard N. Current, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1955), at 273.

[37] Ibid at 274.

[38] David M. Silver, Lincoln’s Supreme Court (Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press, 1956), at 203.