By Zach Klitzman

“If there are any abroad who desire to make this the land of their adoption, it is not in my heart to throw aught in their way, to prevent them from coming to the United States.” Abraham Lincoln

After his election to the presidency in November of 1860, Abraham Lincoln embarked on a 12-day journey from Springfield, Illinois to Washington, D.C. Along the way he stopped in dozens of towns and cities, giving speeches at many of them. One such speech was to a crowd of German-born Cincinnatians on February 12, 1861. Couching his remarks in the vein of universal brotherhood of man, he stated that “while man exists, it is his duty to improve not only his own condition, but to assist in ameliorating mankind.” Specifically, he believed there should be no hinderances to those looking to improve themselves by coming to America: “If there are any abroad who desire to make this the land of their adoption, it is not in my heart to throw aught in their way, to prevent them from coming to the United States.”[1] Lincoln believed in the promise of America, and he viewed it as a promise that all could partake in, regardless of national origin.

Lincoln’s political rise perfectly mirrored an increase in immigration. The United States has always been “a nation of immigrants,” dating back to the colonization period and early Republic era when borders were relatively fluid (especially within the British Empire). Though immigrants arrived on the new nation’s shores every year during its first seventy years, the first massive wave of immigration occurred in the late 1840s and 1850s. In response to famine, failed revolutions, and economic hardships caused by industrialization, millions of immigrants came to the U.S, doubling the foreign-born population from 1850-1860. In fact, after that decade, the foreign-born population stood at 13{f8375f47ae67af23d41895d389f5f1bd2473dc9169ad9eb3f7b4c1f331050350} of the total population in 1860, the same percentage as in 2017, according to the Census Bureau.[2] Foreign-born soldiers played a key role in the Civil War. About one-quarter of the Union armed forces were foreign born and, according to one study, approximately 10{f8375f47ae67af23d41895d389f5f1bd2473dc9169ad9eb3f7b4c1f331050350} of immigrants in 1864 immediately enlisted.[3] Although Lincoln had relatively little personal experience with immigrants in his formative years, he expressed full support of immigration throughout his political career.

An 1862 photo of members of “the Irish Brigade” in Harrison’s Landing, Virginia. Approximately 200,000 Irishmen fought in the U.S. Civil War.

A review of Abraham Lincoln’s speeches, writings, and political actions confirms he was dedicated to the idea of free and open borders throughout his political career. Abraham Lincoln identified at first with the Whig party. The Whigs espoused a vision of America built on a manufacturing-focused economy and were antislavery for the most part, hence Lincoln’s attraction. However, it was often tarred by its Democratic opposition as nativist and anti-Catholic, attacks which were both overstated by Democrats, and not entirely absent from certain strains of the party. For instance, in the aftermath of a May 1844 riot in Philadelphia between nativists and Catholics, Democrats accused the Whigs of stirring anti-immigrant feelings. In response, Lincoln and other Whigs in Springfield, Illinois held a public meeting in June to discuss the riots. At the meeting, Lincoln proposed several motions condemning the riots, stating that the Whigs supported the right of both Protestants and Catholics to practice their faith, and that naturalization laws should make citizenship “as convenient, cheap, and expeditious as possible.” According to the Democratic Illinois State Register “Mr. Lincoln expressed the kindest, and most benevolent feelings towards foreigners; they were, I doubt not, the sincere and honest sentiments of his heart.” The correspondent still took a partisan shot at Lincoln, “Mr. Lincoln also alleged that the whigs were as much the friends of foreigners as democrats; but he failed to substantiate it in a manner satisfactory to the foreigners who heard him.”[4]

Though nativist sentiment had been embedded in this nation since its founding, it reached its antebellum climax with the creation of the “Know Nothing” Party in the mid-1850s. Focusing on issues, such as nativism and temperance, that the two main political parties, Whigs and Democrats, avoided or failed to take seriously, the party could claim by early 1855 10,000 lodges and one million members. Furthermore, the northern wing of the Know Nothing party also was anti-slavery, which attracted certain Whigs who opposed the practice’s expansion, while also possessing some sympathy towards nativism and/or temperance. (The southern wing of the Know Nothings did not endorse antislavery; without that differentiating factor from existing political parties, the party was not as successful in attracting new members in the South as it was in the North.) Originating in New York in 1850, the party elected eight governors, 100 congressmen, mayors of Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago, and other officials across the country in the mid-1850s.[5]

A sheet music cover of pro-Know Nothing “quick step” from the 1850s. All the imagery on the cover is of flora and faun native to America, i.e. non-European.

Lincoln, for his part, denounced the Know Nothing platform, writing to his friend Joshua Speed in August 1855 “I am not a Know-Nothing. That is certain.” He went to on to decry Know Nothing hypocrisy over claiming to be anti-slavery while being viciously anti-immigrant. “How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people?… When the Know-Nothings get control, [the Declaration of Independence] will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.’” Showing his complete contempt of nativist thinking, he ended with a zinger. “When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.”[6]

In 1858, Lincoln debated incumbent U.S. Senator Stephen Douglass in a bid to take his seat. Lincoln ended a speech made in response to one of Douglas’s, by proclaiming that all men, regardless of their national origin, were guaranteed the freedoms promised in the Declaration of Independence. “They have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote the Declaration, and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of the men throughout the world.”[7]

Lincoln failed to defeat Douglas, but he maintained his commitment to immigrant rights. In 1859, a concerned German citizen asked Lincoln his thoughts on a controversial measure that would force newly naturalized citizens to wait two years to vote. Lincoln was against such a measure, in part due to his commitment to treating all men equally. “I have some little notoriety for commiserating the oppressed condition of the negro; and I should be strangely inconsistent if I could favor any project for curtailing the existing rights of white men, even though born in different lands, and speaking different languages from myself.”[8]

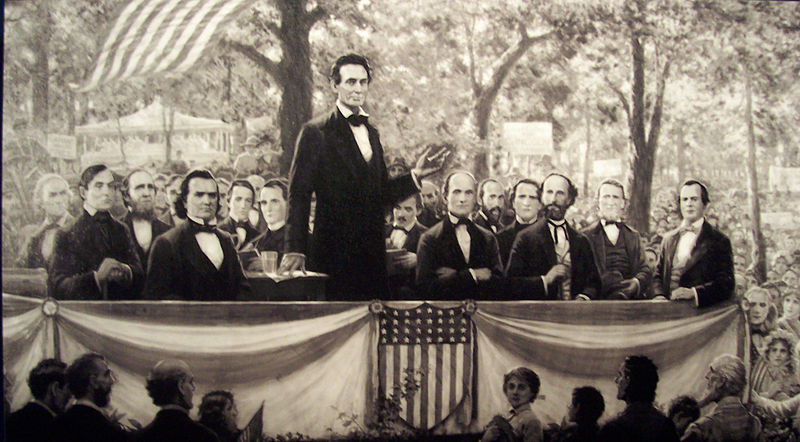

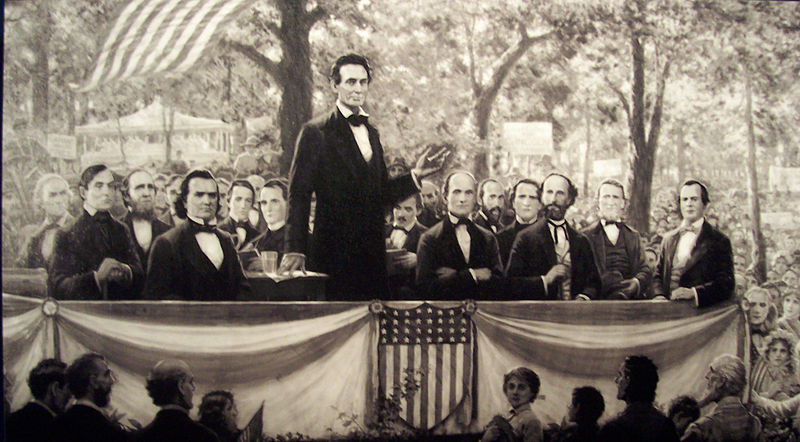

Recreated image of a Lincoln and Douglass debate

Despite his setback in running for the U.S. Senate, Lincoln emerged as a dark horse candidate to become the Republican nominee for the Presidency in 1860. At the nominating convention in Chicago that year, the Republican Party adopted a 16-plank platform, with a heavy emphasis on preventing slavery from expanding further than it already existed. Towards the bottom of the platform (plank 14), they stated “the Republican party is opposed to any change in our naturalization laws or any state legislation by which the rights of citizens hitherto accorded to immigrants from foreign lands shall be abridged or impaired; and in favor of giving a full and efficient protection to the rights of all classes of citizens, whether native or naturalized, both at home and abroad.”[9] The day after the convention, Lincoln formally responded to the Republican National Committee, giving “my profoundest thanks for the high honor done me,” and stating that “the platform will be found satisfactory, and the nomination [gratefully] accepted.”[10] Heading into the pivotal presidential election of 1860, Lincoln’s Republican Party fully supported the rights of immigrants.

Lincoln’s chances at winning the election and defeating the other three candidates appeared slim at first. Indeed, Lincoln failed to win a single southern state (and was not even on the ballot in ten of them). In the end, he swept the North and won the Presidency. Though historians throughout the intervening 170 years have argued how much affect the immigrant vote had on Lincoln’s election, he nonetheless did quite well with foreign-born populations, especially in the Midwest. The secession of southern States began prior to Lincoln’s inauguration; coupled with the Civil War commencing six weeks into his presidency, his attention was on the constitutional crisis, not the issue of immigration. But as the war dragged on, and the nation’s manpower came under immense strain, the issue of immigration rose in prominence.

In his December 1863 message to Congress, Lincoln urged Congress to pass a legislative package “establishing a system for the encouragement of immigration.” Stressing the expediency of the issue, he described immigration as a “source of national wealth and strength,” which could alleviate “a great deficiency of laborers in every field of industry, especially in agriculture and in our mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals.” He believed that “tens of thousands of persons, destitute of remunerative occupation, are thronging our foreign consulates, and offering to emigrate to the United States if essential, but very cheap, assistance can be afforded them,” and concluded that “This noble effort demands the aid, and ought to receive the attention and support of the government.”[11]

Republican-controlled Congress responded to Lincoln’s message quickly. A week after Lincoln’s message, a bill was presented in the Senate, then referred to a special committee for review. An official bill to establish a formal Bureau of Immigration was introduced shortly after the New Year, and eventually passed by the Senate on March 2. Though the House was not as fast to pass its version of the bill, An Act to Encourage Immigration became law on July 4, 1864, the day Abraham Lincoln took up residence at the Cottage for what would be his third and final season. Throughout the debate on the bill, Senators and Congressmen alike echoed Lincoln’s remarks that an increased population of immigrants could aid the American economy. In fact, one Congressman went so far as to say “in twenty years the results of the labors of the immigrant and their children will add to the wealth of the country a sum sufficient to pay the entire debt created by this war.”[12]

The law authorized Lincoln to appoint a Commissioner of Immigration, who would establish regulations for encouraging immigration. One such regulation was to allow immigrants to sign contracts whereby they would relinquish their wages in reimbursement to the government for passage, though the act was clear to state that such an agreement would not create “in any way the relation of slavery or servitude.” It also allowed new immigrants to enroll in the armed forces, but only if a potential recruit “voluntarily renounce under oath his allegiance to the country of his birth, and declare his intention to become a citizen of the United States.[13] A month after signing the bill, Lincoln formally requested that Secretary of the Treasury William P. Fessenden deposit $25,000 of the Treasury in the State Department’s coffers to fund this bill.[14]

A month before the bill became law, the Republican Party held their quadrennial convention in Baltimore (under the banner of the “National Union Party”). When the Party agreed to their platform in 1864, yet again a plank defended immigration. Moving up from 14, this time Plank 8 read: “Resolved, That foreign immigration, which in the past has added so much to the wealth, development of resources and increase of power to this nation, the asylum of the oppressed of all nations, should be fostered and encouraged by a liberal and just policy.” Though being just eighth on the list might seem like it was still a low priority, all seven previous planks were directly or indirectly related to the Civil War. Thus, the immigration plank was the first to stand on its own merits.[15] On June 9, 1864, Lincoln received word that he had been renominated. Upon acknowledging the vote, he yet again endorsed the party’s Platform, including the immigration plank.

A pro-immigration cartoon from the 1880s, touting benefits of America, including “no compulsory military service.

In the fall of 1864, during his reelection campaign, Lincoln continued to promote immigration. In a Proclamation of Thanksgiving in October of 1864 (ahead of the November holiday), he stated that God “has largely augmented our free population by emancipation and by immigration, while he has opened to us new sources of wealth, and has crowned the labor of our working men in every department of industry with abundant rewards.” The influx of immigrants from around the world had swelled the chorus of Union just as recently emancipated freedmen had done.[16]

In December 1864, Abraham Lincoln raised the topic of immigration directly one last time in his final Annual Message to Congress. He asked Congress to enhance the Act to Encourage Immigration, specifically the safeguards to prevent fraud in the immigration process, as well as coercion into the military. He believed this was necessary to aid immigrants, especially since other nations also encouraged emigration. “A liberal disposition towards this great national policy is manifested by most of the European States, and ought to be reciprocated on our part by giving the immigrants effective national protection.” This was not a mere political ploy, but rather a reflection on Lincoln’s deep-seated commitment to immigrant rights. “I regard our emigrants as one of the principal replenishing streams which are appointed by Providence to repair the ravages of internal war, and its wastes of national strength and health. All that is necessary is to secure the flow of that stream in its present fullness.”[17] Lincoln saw the country as a beacon of hope for all seeking freedom and opportunity and he believed the steady arrival of people drawn to the country’s founding ideals and opportunities were crucial to the success of the American experiment.

Zach Klitzman is the Executive Administrator and Editor at President Lincoln’s Cottage.

Footnotes

[1] Roy P. Basler, ed. The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 4:201-203 (hereafter “CW”).

[2] Sabrina Tavernise, “U.S. Has Highest Share of Foreign-Born Since 1910, With More Coming From Asia,” New York Times, September 13, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/us/census-foreign-population.html.

[3] Harold Holzer and Norton Garfinkle, A Just and Generous Nation: Abraham Lincoln and the Fight for American Opportunity. (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 78.

[4] CW 1:237-238.

[5] Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothing and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 5.

[6] CW 2:323.

[7] CW 2:499-500.

[8] CW 3:380.

[9] “Republican Party Platform of 1860,” American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/republican-party-platform-1860.

[10] CW 4:51.

[11][11] CW 7:40.

[12] For more on the congressional debates concerning this bill, including quote on war debt, see Jason Silverman “Lincoln’s ‘Forgotten’ Act to Encourage Immigration,” The Proclamation, July 1, 2016, https://www.lincolncottage.org/lincolns-forgotten-act-to-encourage-immigration/.

[13] 38th Congress Sess. 1 Chapter 246, page 385-396 https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/38th-congress/session-1/c38s1ch246.pdf .

[14] CW 7:489.

[15] CW 7:382.

[16] CW 8:55.

[17] CW 8:141.