By Zach Klitzman

“To give the victory to the right, not bloody bullets, but peaceful ballots only, are necessary.” -Abraham Lincoln

On May 29th, 1856, a group of political leaders from Illinois gathered in Bloomington to discuss the formation of an Illinois Republican Party. Not to be confused with earlier Republican Parties, this iteration was established in 1854 in Wisconsin in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and was fundamentally antislavery. The Act, which allowed the titular territories to vote whether they should be free or slave, upon entering the Union as states, supplanted the Missouri Compromise, which had prohibited slavery in those same areas. Now, in Bloomington, after creating a party platform that denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the expansion of slavery in general, the convention ended with an extemporaneous speech from Abraham Lincoln. It may have been one of the best speeches of Lincoln’s career. One delegate to the convention said, “Never was an audience more completely electrified by human eloquence. Again and again, during the delivery, the audience sprang to their feet, and by long-continued cheers, expressed how deeply the speaker had roused them.”[1]

Though contemporaries make clear the speech was mesmerizing in its denouncement of slavery, no contemporary word-for-word description of Lincoln’s ninety-minute oration remains. Though one newspaper provided a brief overall synopsis, an accurate rendering of “Lincoln’s Lost Speech” does not exist, making it one of the few public speeches of Lincoln for which no written or transcribed version exists. There have been several recreations of this speech, including one in 1896 by Henry Clay Whitney, who claimed to have used contemporaneous notes of the speech. Though his recreation was deemed “not worthy of serious consideration” by the editors of the definitive The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, one part of the speech has entered the lexicon of memorable Lincoln quotes, despite its questionable word-for-word accuracy. In referring to the ongoing crisis, Lincoln urged that the issue could still be decided by level-headed decisions that eschewed violence. According to Whitney’s version of the speech, Lincoln said: “Do not mistake that the ballot is stronger than the bullet. Therefore let the legions of slavery use bullets; but let us wait patiently till November, and fire ballots at them in return; and by that peaceful policy I believe we shall ultimately win.”[2]

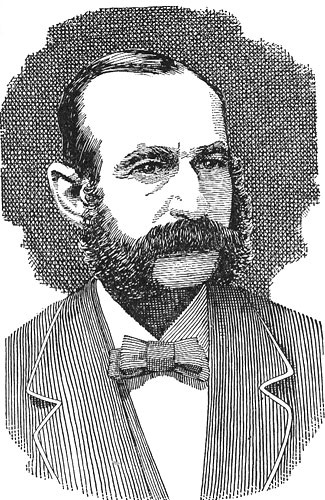

Henry Clay Whitney, who published a version of Lincoln’s so-called “Lost Speech.”

“The ballot is stronger than the bullet” has entered the popular imagination as a powerful Lincoln saying. It even inspired a musical composition commissioned by NPR.[3] Its poignancy is further emphasized by the fact that Lincoln was assassinated just a few months after being reelected. Would his second term have had a more positive impact on American history than what happened after his assassination? We’ll never know. Even if the exact phrase is perhaps a bit exaggerated by Whitney, the sentiment is thoroughly Lincolnian. Throughout his life, in both his own writings and in others’ recollections of the president, this theme of voting having more power than violence holds steady, as does his commitment to the importance of free and fair elections.

The most definitive quote from Lincoln promoting ballots over bullets is a fragment of a speech dated December 1857, which possibly was related to a May 1858 speech. It was a response to the Dred Scott decision, which found that African Americans had no rights, and could not be citizens. Lincoln used the decision as further proof that the nation was heading towards some sort of major conflict, inserting the biblical phrase “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” which was to be the backbone of his famous speech in June 1858. In this speech fragment, he wrote that the country had not yet reached the point of bloodshed because, “To give the victory to the right, not bloody bullets, but peaceful ballots only, are necessary. Thanks to our good old constitution, and organization under it, these alone are necessary. It only needs that every right-thinking man, shall go to the polls, and without fear or prejudice, vote as he thinks.”[4]

After winning the presidential election, he repeated this message of ballots over bullets in his message to Congress, in their emergency session in July 1861. Writing on the 85th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, he said that the Union must “demonstrate to the world that those who can fairly carry an election can also suppress a rebellion; that ballots are the rightful and peaceful successors of bullets; and that when ballots have fairly and constitutionally decided, there can be no successful appeal back to bullets; that there can be no successful appeal except to ballots themselves, at succeeding elections. Such will be a great lesson of peace; teaching men that what they cannot take by an election neither can they take by a war; teaching all the folly of being the beginners of a war.”[5] Ballots over bullets, brains over brawn, that is what Lincoln hoped to utilize to end slavery.

Lincoln evoked ballots over bullets throughout his presidency since the very fundamental bedrock of the nation’s democracy was under attack. In 1861, the United States had only been in existence 85 years, and was still a unique experiment in democracy. The world was watching, and many non-Democratic countries expected — even hoped — the Civil War would lead to the ruin of the United States. For instance, an official in Napoleon III’s government remarked to an American visitor in March 1861, “No Republic ever stood so long, and never will. Self-government is a Utopia, Sir; you must have a strong Government as the only condition of a long existence.” A few years later, Walt Whitman remarked “there is certainly not one government in Europe but is now watching the war in this country, with the ardent prayer that the United States may be effectually split, crippled and dismembered by it. There is not one but would help towards that dismemberment, if it dared.”[6] Lincoln understood the precarious situation of the country, that if the Union failed, so to would the worldwide example of American democracy. Thus, he had to stay committed to the nation’s republican and democratic principles.

In addition to quotations from Lincoln himself, there are other examples of Lincoln associates recollecting his conviction that democratic elections were the best tool for lasting change — not violence. For example, his former law partner William Herndon claimed that in 1855 Lincoln told a group of abolitionists, “You can better succeed with the ballot. You can peaceably then redeem the government and preserve the liberties of mankind through your votes and voice and moral influence…. Revolutionize through the ballot box and restore the government once more to the affections of hearts of men by making it express, as it was intended to do, the highest spirit of justice and liberty.”[7] Sometime after his nomination as the Republican candidate, he was alleged to have said to Tom Henderson, an Illinois politician, “I do not believe this arising trouble will be settled by arms but by the ballot. Pledge yourselves that if I fall before it is over, you will carry this in by the ballot.”[8]

In addition to his words, Lincoln’s actions — both verifiably bona fide and potentially apocryphal—demonstrated his belief that elections were fundamental to democratic society. The Civil War was probably the one time in American history where there would have been a reason with a potentially constitutional defense to postpone an election. Yet Lincoln, even when it looked like his reelection chances were doomed, remained committed to a fair election at the prescribed time. He had taken a similar approach to the construction of the Capitol Building. “If people see the Capitol going on, it is a sign we intend the Union shall go on,” he said in 1862.[9] And so it was with the president election of 1864. In the aftermath of his reelection, he responded to a serenade at the White House with a reflection on the importance of the recent balloting: “the election was a necessity.” After all “We can not have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us.”[10]

Lincoln viewed the unfinished Capitol dome (depicted here in 1862) as a metaphor for the progress of the War.

Though Lincoln decried armed rebellion when a portion of the electorate was unhappy with the results of a free and fair election, he nonetheless took advantage of the Civil War’s effect on elections. When the western counties of Virginia sought to secede from the rest of the state and rejoin the Union, they needed approval from the state legislature. Since the Virginia legislature based in Richmond obviously opposed such a move, representatives from the countries formed a rump legislature and voted themselves separate. Lincoln approved this body’s decision, even if the majority of the state’s antebellum voting population did not vote because “it is not the qualified voters, but the qualified voters, who choose to vote, that constitute the political power of the state.”[11] For Lincoln, refusing to show up to vote was tantamount to surrendering one’s civic rights. He did not believe that remaining outside of the political world helped one’s caused. (Compare this to the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, for example, who urged his followers that all voting did was propagate the unjust slave system. Instead he promoted “public agitation.”[12])

In addition to remaining committed to free and fair elections in contentious times, Lincoln also demonstrated his support of voting rights when it came to two marginalized groups in particular: immigrants, and formerly enslaved men.[13] Of the two, he was more consistently supportive of the former. But over the course of the war, he became more open to and accepting of the idea of black suffrage.

On Election Day November 2, 1852, Lincoln and two other Whig lawyers in Springfield Illinois, published an editorial clarifying Illinois election law. A Democratic newspaper had spread a rumor that Whigs were attempting “to prevent our adopted citizens from voting to-day.” Lincoln, who was supportive of immigration throughout his life, clarified that such voter suppression was not allowed. After reviewing the relevant state laws, “We are of opinion that any person taking the oath prescribed in the act of 1849, is entitled to vote.” Furthermore, any challenge to such a citizen’s right to vote must be agreed upon by a majority of judges, not just a single contested claim. The introductory text to Lincoln’s remarks made clear that having naturalization papers was “the shortest and easiest way of doing the thing up, in case of a controversy,” even if “having the Naturalization papers at the polls is not indispensably necessary.”[14] Later that decade, Lincoln was asked his opinion on a controversial Massachusetts law that required naturalized citizens to wait two years before they could vote. In response to the letter he wrote that he opposed its adoption in Illinois on the principle that “the spirit of our institutions [is] to aim at the elevation of men,” and thus he was “opposed to whatever tends to degrade them.”[15] Lincoln’s words speak volumes about the dignity he bestowed on white male citizens.

As to African American suffrage, Lincoln’s words were more mixed over his career, yet towards the end appeared to point towards acceptance. In a speech on June 26, 1857, Lincoln lamented the recent Dred Scott decision. Building his argument that Dred Scott was another sign that the state of Blacks in America was “hopeless,” he used the example that states have restricted the franchise from free blacks, with both New Jersey and North Carolina eliminating previously granted rights entirely. Furthermore, “it has not been extended…to a single additional State, though the number of states has more than doubled.”[16] For Lincoln, the right to vote was paramount to a successful public life, and thus not having it was a sign of hopelessness – even if he personally did not support full suffrage for Blacks quite yet.

In fact, prior to his time as President, Lincoln often had to go on the defensive, asserting that he was not in favor of complete equality between the races, including suffrage rights. In 1858 he famously replied in response to race-baiting from Stephen Douglas “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes…”[17] Such a response, while disappointing to today’s readers with the benefit of 150 years of hindsight, was just that: a response to an attack meant to harm him. Despite the potential votes to be gained by denigrating African Americans, Lincoln never actively campaigned on such views as many of his contemporaries did. Furthermore, the cataclysm of the Civil War would significantly change his views.

Recreated image of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Douglas often put Lincoln on the defensive with race-baiting accusations.

In an undated letter to Union General James Wadsworth that was published five months after his assassination, he spoke of bestowing suffrage to the formerly enslaved in return for amnesty of former Confederates. “You desire to know, in the event of our complete success in the field, the same being followed by a loyal and cheerful submission on the part of the South, if universal amnesty should not be accompanied with universal suffrage. … I cannot see, if universal amnesty is granted, how, under the circumstances, I can avoid exacting in return universal suffrage, or at least, suffrage on the basis of intelligence and military service.”[18]

In March 1864 he gave his strongest support to black suffrage yet, albeit in a private letter. Writing to the newly elected governor of Louisiana, he suggested the new state constitution give certain freedmen the franchise, “for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks.” For Lincoln, this suggestion was not just to reward soldiers’ service, but to permanently strength democracy and liberty. These newly enfranchised voters “would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom.”[19]

Finally, and tragically, on April 11, 1865 in his last public address Lincoln indicated his preference for black suffrage. Referring to the reconstruction efforts in Louisiana, he said “It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.”[20] Unfortunately, he never saw this preference in action. One person in the crowd heard this speech, and commented to a friend “that means N—– citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make.” And so it was, for that spectator was John Wilkes Booth.

***

Throughout Lincoln’s life, his letters, speeches, and actions reflected his steadfast view that free and fair elections were fundamental. He understood that the experiment of American democracy required the country to continue elections regardless of calamities like the Civil War. To postpone or ignore such civic duties would jeopardize the nation’s basic premise. As to voting rights, Lincoln did engage in what we might call “identity politics” today. While he was not always “progressive” by today’s standards, he nonetheless espoused certain broad interpretations of the franchise. In defending (male) immigrants’ rights to vote, and later supporting the idea of suffrage for black men who had served in the Union army, he demonstrated support of a wider franchise than some of his contemporaries defended. In the end, Lincoln’s unwavering commitment to ballots over bullets proved to be ironic as he was assassinated for suggesting more Americans should have access to ballots. Yet in the decades since Lincoln’s untimely death, suffrage has expanded well beyond what Lincoln himself promoted, even though it hasn’t been without violence and retrenchment from those who would seek to limit it. With each generation, there are new ideas and new movements seeking changes to that most fundamental element of our democracy — elections.

Zach Klitzman is the Senior Executive Assistant at President Lincoln’s Cottage.

Footnotes

[1] Roger J. Norton, “Abraham Lincoln’s Lost Speech,” Abraham Lincoln Research Site, accessed 1/23/2019. https://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln63.html.

[2] Henry Clay Whitney, Abraham Lincoln’s lost speech, May 29, 1856. New York: 1897, 46.

[3] Tom Hueizenga, “Sing Out Mr. President: Honest Abe, Bullets and Voting Booths, NPR February 11, 2011. https://www.npr.org/sections/deceptivecadence/2011/02/20/133594257/sing-out-mr-president-honest-abe-bullets-and-voting-booths.

[4] Roy P. Basler, ed, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 2:454 (hereafter “CW”).

[5] CW 4:439.

[6] Quotes from Don H. Doyle, The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War, (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 1 and 8. Doyle’s book is a great analysis of the international perspectives of the Civil War.

[7] Don Edward Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher. Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1996), 246.

[8] Fehrenbacher and Fehrenbacher 236.

[9] https://uschs.wordpress.com/2013/02/12/abraham-lincoln-and-the-capitol-dome/

[10] CW 8:100-102.

[11] CW 6:27-28.

[12] Nick Sacco, William Lloyd Garrison and the Principle of Non-Voting, November 5, 2014, https://pastexplore.wordpress.com/2014/11/05/william-lloyd-garrison-and-the-principle-of-non-voting/.

[13] On women’s suffrage, Lincoln was silent for the most part.

[14] CW 2:160.

[15] CW 3:380.

[16] 2:403-404.

[17] CW 3:145.

[18] CW 7:101

[19] CW 7:243.

[20] CW 8:403