The U.S. and Juneteenth flags flying (c/o Flickr user 2011 Juneteenth Celebration)

As a nation we can celebrate January 1, 1863, as the day Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation took effect and declared freedom for 3.5 million of America’s slaves held in rebellious areas. December 6, 1865 is an occasion worthy of celebration, too. That is the day Georgia ratified the 13th Amendment thereby making this measure of abolition a part of our Constitution. These twin federal death knells for slavery are only part of the story, though. Emancipation had been an ongoing process in the United States since the Declaration of Independence.

Pennsylvania passed its Gradual Abolition Act in 1780 while the Revolutionary War was still raging. Under the Articles of Confederation, slavery was banned from the Northwest Territory. New York celebrated the final emancipation of slaves within its borders on July 4, 1827. During the Civil War, Missouri and Maryland abolished slavery via state action.

In Texas, the celebration of emancipation takes place on June 19th and centers on the port city of Galveston.

The Battles for Galveston

Although removed from most of the action of the Civil War, Texas from time to time appeared in the military limelight of the war. Texan units of the Confederate military led an invasion of New Mexico in early 1862 that threatened to detach the entire southwest from the Union. Although thwarted, the Union southwest remained under threat of invasion. In addition, the French imperial war against Mexico’s republican government worried the Lincoln administration, which wanted to show as much support as possible for the beleaguered Mexican democracy by having a Union military presence in Texas. Lastly, the port of Galveston, although under Union blockade, remained under Confederate control and could be used by blockade runners to receive aid from foreign governments.

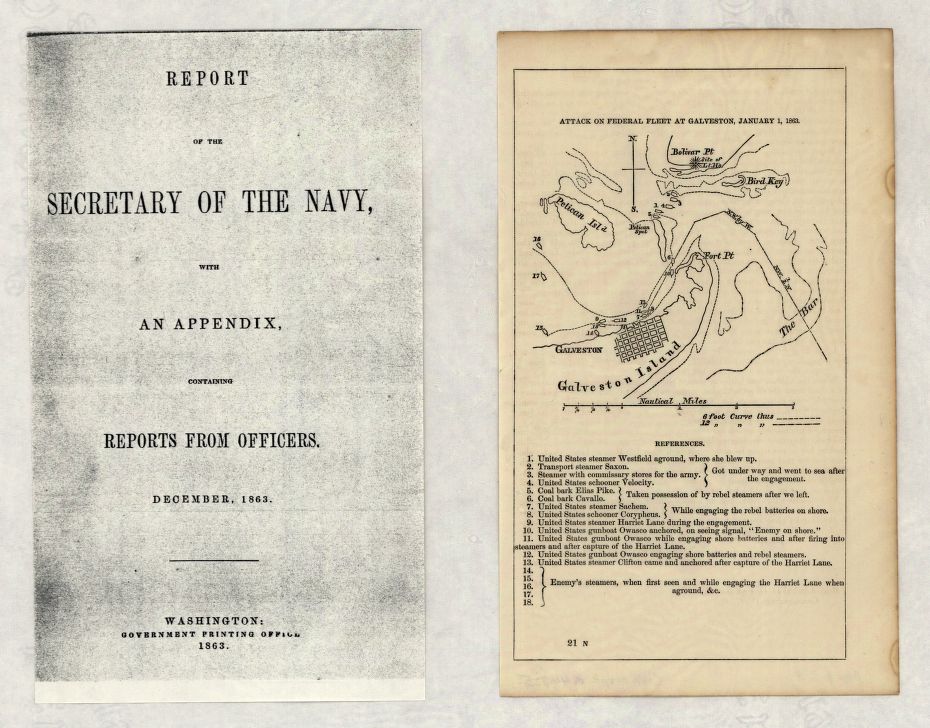

Report on the January 1, 1863, Battle of Galveston (c/o the Library of Congress)

These factors led the U.S. Navy to descend upon Galveston on October 4, 1862, just two weeks after President Lincoln’s announcement of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The U.S. Navy after some minor shelling managed to strike a deal with the Confederate forces allowing them to peacefully evacuate Galveston. With that the U.S. Navy occupied a major Confederate port.

The occupation did not last long, however. On January 1, 1863, as President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, the Confederacy launched a counter-attack on Galveston. A series of Union blunders led U.S. troops on the island city to think their naval comrades were abandoning them, so they surrendered without much of a fight to the Confederate attackers. Galveston thus remained beyond Union control for the rest of the war, although the blockade persisted. For the 250,000 enslaved people in Texas, the loss of this Union toehold was a disaster for their hopes of freedom. Instead having a nearby refuge to flee to, they would have to depend on developments elsewhere in the country to eventually deliver emancipation.

Emancipation at Last

Victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in July 1863, Sherman’s March and Lincoln’s re-election in the fall of 1864, and Grant’s capture of Richmond in April 1865 brought about the national victories needed to bring emancipation to the Lone Star State. Federal forces once again landed in Galveston and finally re-established constitutional authority in Texas on June 18, 1865, two-and-a-half years after the Emancipation Proclamation had declared the enslaved persons “forever free” in rebel-controlled Texas.

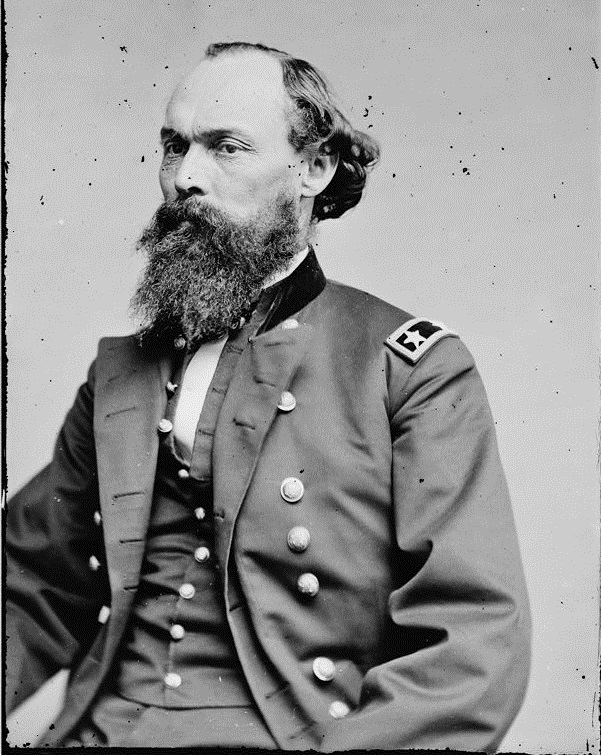

Gordon Granger (c/o the Library of Congress)

The next day, June 19, Major-General Gordon Granger stepped out on the balcony of the Ashton Villa, a home that previously served as the headquarters for the rebel army in the region during the war, and read General Orders No. 3:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Ever since this momentous declaration, June 19th been celebrated as Emancipation Day in Texas with the unique and distinctive moniker of “Juneteenth.” As black Texans quickly took to their freedom from slavery, vexing questions of labor, civil, and political rights still hovered over the state and the nation. Only in 1870 after Congress refused to seat any congressmen from the state did Texas ratify the 14th and 15th Amendments, which protected citizenship and voting rights of black Americans. The same begrudging, belated acceptance of emancipation and citizenship for African Americans led to sharecropping replacing enslavement as the mode of controlling the black Texan population.

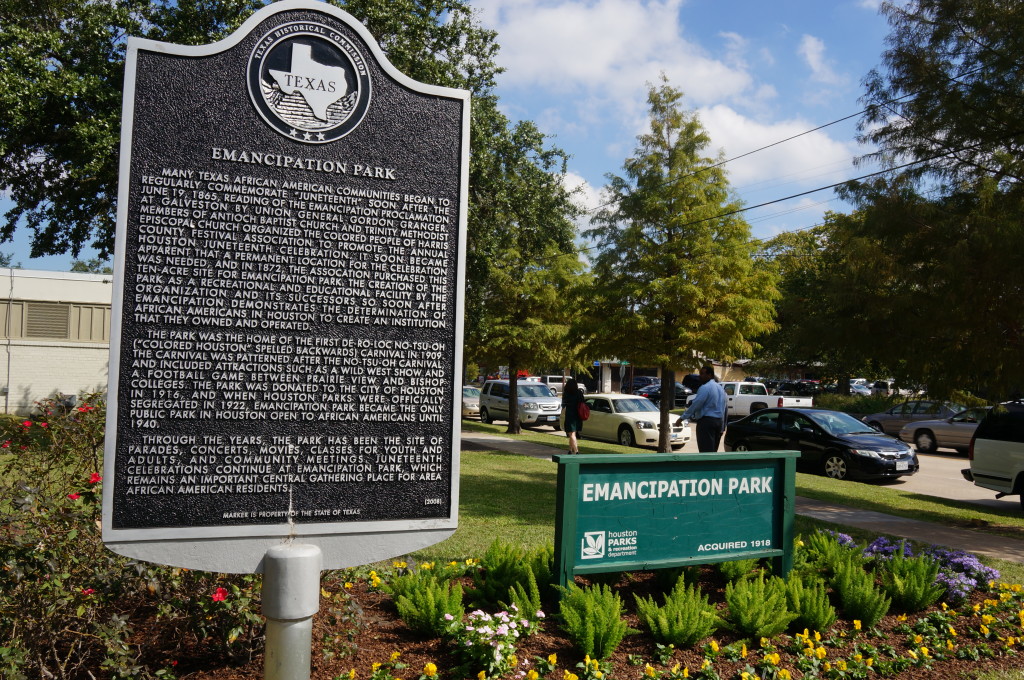

Despite the continuing repression of their civil and political rights, African Americans in Texas continued to celebrate Juneteenth. In communities across the state, freedmen pooled money together to purchases plots of land and set them aside as “emancipation parks.” One such instance occurred in Houston, not far from Galveston, in 1872 and the park remains to this day known as Emancipation Park.

Emancipation Park in Houston (c/o Defender Network)

Typical celebrations of Texas’s Emancipation Day including readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, barbecue, dancing, singing, and poetry recitations as the day grew into a wider celebration of black culture in Texas. The great migrations of the 20th century of black Texans to the Midwest and California helped spread the holiday to new regions of the country. After a century of observance by the state’s black population and a renewed push for civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s, the Texas legislature officially made Juneteenth a state holiday in 1980. Today the holiday remains one of the many reminders of the complex history of emancipation and freedom in the United States.