“If individuals in a society invested in each other, for the good of each other, then that society would surely flourish.” -Kelvin Smith, CIAW member and NCI resident

Cadell “Monty” Kivett is the kind of person you could talk to for hours without realizing any time has passed.

As we’ve gotten to know one another, Monty has told me all about his amazing life—from riding the rails across America with the Ringling Brothers Circus, to playing live music with a few bands, to fifteen years in the tattoo industry, which he says taught him more about art than any other experience. Monty is—among many other things—a writer, a scholar, an artist, and a community organizer with a clear vision for a more equitable and just future. Monty is also presently incarcerated at Nash Correctional Institute (NCI) in Nash County, North Carolina.

Monty’s creative pursuits and community organizing have carried over from his life on the outside to his life at Nash. He is the former editor of and a regular contributor to the Nash News, a publication managed, compiled, edited, and printed by incarcerated men at Nash since 2005. Articles in the Nash News range from thoroughly researched pieces on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on incarcerated populations to reviews of recent events like the annual NCI Christmas pageant. Each issue also spotlights the work of one or more of NCI’s many talented artists.

A cover of a 2018 issue of the Nash News.

It is thanks to the Nash News and its focus on art that we here at Lincoln’s Cottage have had the opportunity to work with Monty, who is the curator and project manager for our current exhibit, Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project. Prison Reimagined is a collaboration between the Committee of Incarcerated Artists and Writers (CIAW)—a panel of eleven incarcerated men at Nash, including Monty—the Justice Arts Coalition (JAC), and the Cottage.

In 2020 the Nash News did a feature on JAC founder and director, Wendy Jason. When the idea for the Prison Reimagined came to Monty in 2021, he remembered Wendy and immediately wrote her a letter. Thus began a years-long process of planning, organizing, and communication.

Although Prison Reimagined is Monty’s brainchild, he would be the first to mention that the exhibit has been a team effort, a particular feat at NCI where collaboration is often stymied by prison administration and bureaucracy. Kelvin Smith—NCI resident, member of the Lumbee Tribe, and another member of the CIAW—explained to me that,

“Prison is a highly controlled environment, even for those of us who have proven trustworthy. For instance, Nash prison has four housing units in four separate buildings. Each building has 2 blocks. Each block houses 108 men; some of us have single cells (think eight by ten-foot cinder block rooms) and the others live in an open dorm on bunk beds. Typically, we are only allowed to be in the block that we live in.”

As a graduate of the North Carolina Field Minister Program (NCFMP)—one of the few personal and professional development opportunities available to NCI residents—Kelvin can visit with men across the institution during his ministry. Not only has this facilitated exhibit planning, Monty explained, but the involvement of the NCFMP has lent an air of legitimacy to Prison Reimagined in the eyes of NCI staff.

At first glance, this might just seem like interesting background information on how Prison Reimagined came about. However, as a Museum Program Associate (MPA) who is tasked with guiding visitors through the new exhibit, the conversations I have been having with the members of the CIAW are foundational to my ability to interpret the exhibit as thoughtfully and fulsomely as possible.

For the last few months, the MPAs have been communicating with members of the CIAW through text messages via an app called Getting Out, which allows incarcerated individuals to stay in touch with their friends and relatives on the outside. As my fellow MPA, Jacob Wilson, described the experience, “to be able to work with individuals that suffer under this [carceral] system and to bring their insights to the public has been an honor.”

The process hasn’t been without its challenges. The app is unreliable—it routinely deletes message drafts, sent messages are sometimes delayed by up to two weeks, and of course it costs money to send each message, which can be a significant barrier to this sort of forward-thinking, collaborative work. As Jacob put it, “to have to pay for the use of a system like Getting Out that is a person’s only means of contact with the people they care about is a crime in and of itself.” We are grateful to have the support of both the JAC and the Art for Justice Fund to help mitigate the cost. Despite the roadblocks, our conversations have been meaningful and will help make your experience of the exhibit even more enjoyable.

Along with the other members of the CIAW, Monty and Kelvin solicited and reviewed each work of art and writing submitted for the exhibit. I have traded messages with them both about our personal interpretations of a handful of the portraits and have shared our respective understandings of the historical and political context for each one.

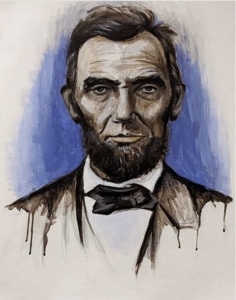

Honest Abe (Change is Possible) by Valentino Amaya is one of Monty’s favorite pieces

Furthermore, Monty has shared some of his research into the history and realities of the American carceral system. He explained that,

“Our prison criminal punishment systems are rooted in and descended from slavery. There are prisons in [North Carolina] that were one-time slave plantations (Caledonia), just as Angola [Prison, in Louisiana] was. And these systems have been doing the same business for so many years, and out of the public’s sight.”

Bringing those systems to light, encouraging our visitors to get curious about the American carceral system, and introducing the artists and CIAW members to our visitors are all goals of the Prison Reimagined exhibit.

Here at Lincoln’s Cottage, we think daily about Abraham Lincoln’s entanglement with the justice and carceral systems in our country via the enduring legacy of both the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution. The 13th Amendment reads, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

We hope you’ll visit the Prison Reimagined: Presidential Portrait Project at the Cottage between January 5th and February 19th to learn more about how those words have historically shaped, and continue to shape our country today, from some of the people they directly impact.

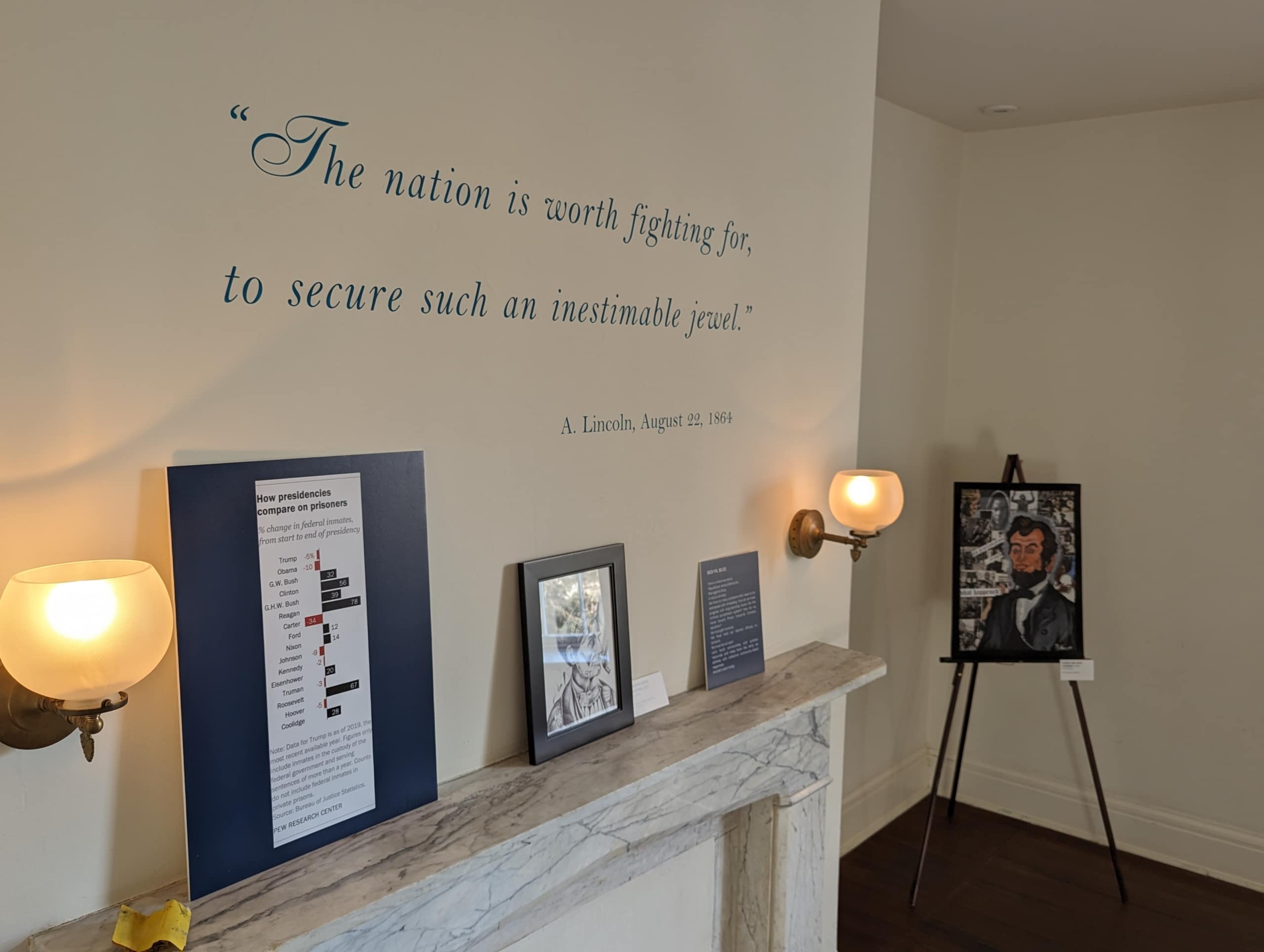

Photo from the exhibit by Conor Broderick

Haley Bryant is a Museum Program Associate at President Lincoln’s Cottage.