By Rae Katherine Eighmey and Erin Mast

Along with their two youngest sons, Willie and Tad, Abraham and Mary Lincoln brought their Midwestern values, habits of charity, and penchant for personal interaction to Washington. The war-challenged city would benefit. In 1862, just over a year after Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, reporter Noah Brooks wrote that there were “a little more than twenty hospitals in churches, the public halls of the Patent House and other public buildings.” Mary Lincoln was known to send food and treats to these hospitals, frequently “re-gifting” items that had arrived in the White House such as citrus fruits. Perhaps not to be outdone in charity work, later in the war Tad launched his own efforts to raise funds for the US Sanitary Commission. When his first efforts were quashed, he set up a stand in the White House lobby, selling beef jerky and fruit to the long lines of people waiting to see his father.[1]

These anecdotes are just two examples of the way food provides a delightful lens into the lives of Abraham and Mary Lincoln. What foods they purchased and from whom, what foods they enjoyed and in what company, and how they shared or gave food to others illustrates who they were as private citizens, how they felt about people around them, and how they viewed their role as the Presidential family during the great tragedy and upheaval of the U.S. Civil War.

From dishes Mary prepared and foods Lincoln enjoyed and shared with others throughout their lives, we have glimpses of their affection for one another, their relationships with people in the community, and the unique demands on, and conflicting expectations of, a President and First Lady to entertain in the midst of war.

In two companion articles, we explore Abraham and Mary Lincoln’s connection to food, beginning with their very different circumstances in life — Abraham Lincoln raised on the frontier, in a family of relatively scarce means, and Mary by contrast, in a wealthy family in Lexington, KY.

In the first article, we focused on Mary Lincoln. In the second part of the series, we look at Abraham Lincoln as revealed through six foods: oysters, turkey, baked beans, soldier’s bread, chicken fricassee, and apples.

Oysters

“I prefer my oysters cooked.”

First, we turn our attention to oysters. Oysters are a food frequently associated with celebration. The first recorded mention of them that we have in relation to Abraham Lincoln was at a celebration in Vandalia, Illinois in 1837. Abraham and the other members of the Sangamon Long Nine — a group of very tall members of the Illinois State Legislature — celebrated their achievement moving the state capital north from Vandalia to Springfield, their home town. At that party, the large group devoured dozens of the bi-valves. And yet it’s not clear how much Lincoln himself partook of that particular oyster feast. Years later, Lincoln was offered raw oysters while on the Illinois campaign trail. He declined, saying he preferred them cooked. Evidence confirms that the Lincolns enjoyed them in some fashion, as oyster shells were found in an old well pit at the Lincolns’ Springfield home. We also know oysters were served for celebrations at the Lincoln White House, including a feast at a reception in February 1862 (covered in the first article) that included both stewed and scalloped oysters, champagne punch, partridge, venison, jellies, cakes, and more.[1] As one visitor reported of another meal, “he handled the spoon just like an ordinary farmer, saying to all in his reach: ‘Will you have some of this.’ And dishing it into our plates liberally.”

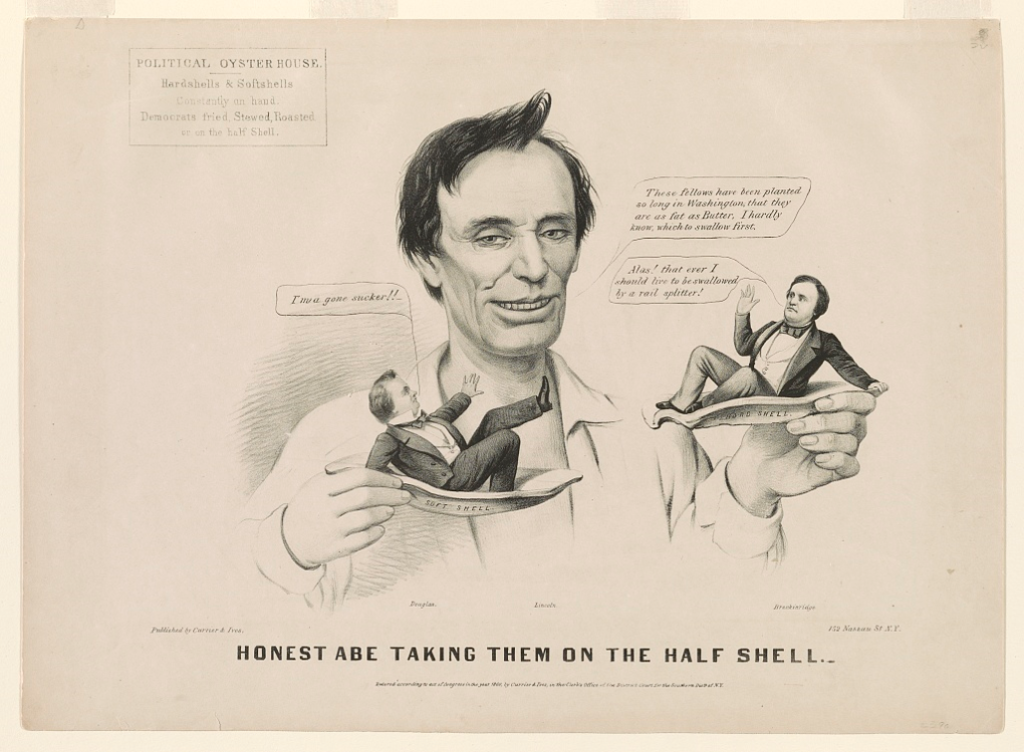

Lincoln was even depicted “eating his opponents” as if they were oysters in a political cartoon in 1860. In the cartoon, Lincoln’s caption reads “These fellows have been planted so long in Washington, that they are as fat as Butter, I hardly know which to swallow first.” Stephen Douglass is depicted on a soft shell as a moderate Democrat, whereas John Breckinridge is on a hard shell as a staunch proslavery advocate.

Abraham Lincoln’s appreciation for oysters even while apparently eschewing the raw ones, reflects his ability to fully engage in a celebration — without taking unnecessary risks.

Turkey

Abraham Lincoln traveled the furthest distance of any president en route to Washington, DC at the time he was elected to office. And he practically ate his way there. In February 1861, Lincoln’s train stopped in seventy-five cities and towns on the way to the nation’s capital. It made 12 overnight stops on the 13-day journey. At each major stop, civic leaders tried to outdo each other with receptions, parties, and balls. Lincoln reportedly took in local fare along the way as well. For example, it was reported that he enjoyed a turkey at Sourbeck House in Alliance, Ohio.

In addition to eating turkey on the road to Washington, DC, Abraham Lincoln set an important turkey-related precedent. The historical record suggests that Tad Lincoln’s pet turkey Jack was the first turkey to be “pardoned” by the President. Unlike the White House Thanksgiving tradition of today however, this was apparently an ad hoc event around Christmas in 1863. As recorded by Noah Brooks, “a live turkey had been brought home for the Christmas dinner, but [Lincoln’s son Tad] interceded in behalf of its life.” Abraham Lincoln’s indulgence toward his sons is well documented, and Tad’s plea was enough to spare the turkey’s life.[2]

Jack the Turkey made another appearance in a classic Abraham and Tad story. Lincoln was the first President to have a standing security detail, the Presidential Guard. The soldiers and cavalry were first assigned to Lincoln at the end of his first season living at the Cottage on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home, and were with the family there and at the White House. He at first resisted the security detail, occasionally taking off in the morning without them. Later, not only did he come to accept them, but he also appreciated the camaraderie they offered to him as well as his youngest son Tad. In the wake of his brother Willie’s death in February 1862 and with his oldest brother, Robert, away at college, having young soldiers nearby provided Tad with welcome company. For example, on election day in November 1864, Tad polled the soldiers to see who they had voted for. Wearing his own uniform, he surveyed the troops and reported to his father that they supported their current commander-in-chief. President Lincoln then asked Tad if Jack had voted. Lincoln took great joy in repeating Tad’s response to anyone who would listen. “Oh no, he’s not of age.”

Abraham Lincoln’s praise of the turkey meal amongst the locals in an Ohio town and his sparing of Jack the Turkey’s life are illustrative of his graciousness to both strangers and family.

Baked Beans

Baked beans were a common 19th-century breakfast dish, and still are in many other cultures. They are easily cooked in a bean pot baked in fireplace ashes overnight, or held over from the previous day’s dinner. They were enjoyed hot or cold. We don’t know if Lincoln wandered down to the kitchen himself, which seems possible given his decidedly informal personality. And he did know how to cook — as a child on the frontier who lost his mother at a young age, knowing how to cook was a survival skill.

Humble foods like baked beans figure prominently in descriptions of Lincoln’s interactions with the Presidential Guard. The Bucktails Sergeant Charles Derickson recalled that President Lincoln used to enjoy coming over to camp for a cup of “army coffee” and “a plate of beans.” Albert Nelson See, another one of the Bucktail soldiers guarding the Lincolns at the Soldiers’ Home and the White House wrote that, “Tad was at our camp almost every day and, very frequently ate dinner at one of our tents. He would get a dish at whatever tent he happened to be at when the bell rang and get in line and draw his rations the same as the rest of us and seemed to enjoy it.”

To a modern reader, the idea of a President eating beans with soldiers may come across as nothing more than a “photo opportunity,” but for Abraham Lincoln, that was part of his authentic, daily life. While Lincoln no doubt appreciated the camaraderie that came with the beans, the president seemed to simply like beans. Dr. Henry Pierce discovered that affinity when he brought his nephew to the White House one day. As he toured his nephew around the Executive Mansion, he was astounded to find the president sitting alone at the table eating a plate of baked beans. A measure of his surprise may have been on how humble the food was, and the fact that Abraham Lincoln was sitting alone. Though the three talked for a bit, the story does not make it clear if Lincoln offered to fetch a few more plates.

Lincoln’s appreciation for baked beans as well as the stories of him eating alone or eating with soldiers, reveal a man who appreciated both solitude and camaraderie — devoid of fanfare — even while occupying the highest office in the land.

Soldier’s Bread

Campfire soldier’s bread

The members of Lincoln’s presidential guard were not career soldiers — few were in the military at the outset of the Civil War. Lincoln had experienced soldiering in his youth, too, though in a decidedly different conflict. At the age of 23 he had served in the wilds of northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin during the summer-long Black Hawk War in 1832. His militia group from New Salem was mustered out after a month. Lincoln re-upped twice. And that brings us to a most humble food, soldier’s bread. In the Black Hawk War, Lincoln and his fellow soldiers frequently had to make do. They raided abandoned farms liberating scrawny chickens into their stew pots. They made flour and water bread and cooked it over the fire by wrapping the dough around their musket ramrods or baked on army-issued grills.

Official issue soldier’s bread

Union Soldiers on the front lines of the Civil War were more familiar with hardtack, a hard, plain cracker a few inches square. Rations for Washington-stationed Union soldiers were decidedly better. All manner of farm goods were sold at markets and even brought out by sutlers to the camps. Lincoln and Tad strolled the Soldiers’ Home grounds and shared campfire meals including the bread baked from the huge army bakery in the City.

Lincoln’s partaking of bread in its simplest forms illustrates that, as President, he was able to draw on his own personal experience with hardship to connect with others.

Chicken Fricassee

“Can you make old fashioned chicken fricassee?”

And yet, despite the relative abundance in DC, Abraham Lincoln could not and would not escape the war. As the war dragged on, the accumulated stresses were evident, and seemed to have an impact on Lincoln’s eating habits. At first, Mary Lincoln employed food and an appeal to her husband’s good nature to get him away from the pressures of the office. She invited old friends and new acquaintances to come to meals, insisting that her husband come out of his office to eat “since they had company.” The rule seemed to be, according to Illinois friend and then Senator Orville Hickman Browning, “that if you were in the White House at mealtime you were invited to sit down.” During one particularly stressful time, it is reported that Mary Lincoln asked the White House cook if she could prepare an old-fashioned chicken fricassee to tempt him into eating. Mary met with limited success. As the war went on, Lincoln got gaunter and more haggard looking, evidence perhaps of a lack of eating properly.

The story of the chicken fricassee illustrates that with Abraham, Mary was facing an uphill battle in trying to ease the great stress he was under as Commander-in-Chief during the Civil War.

Apples

Despite comfort foods and old friends, Lincoln’s appetite dwindled. Frequently he would simply eat an egg, toast, and milk or coffee for breakfast. Lunch was an apple, or biscuit, and milk. Apples feature in a classic Lincoln story, in which he reveals his opinion of those who could only focus on their narrow interests rather than the risks to the nation. He began with his famous introduction: “This reminds me of a story: A riverboat captain was plunging and wallowing along in treacherous boiling current, requiring the captain’s utmost diligence and attention. Where upon a boy pulled on his coat and hailed him with: “Say, Mister Captain! I wish you would just stop your boat a minute — I’ve lost my apple overboard!”

While in the story the apple represents the narrow interest, in his own life, Abraham Lincoln’s enjoyment of apples is well documented. He said that people should eat foods that agreed with them and that apples agreed with him. They were a lifelong favorite. He ate them in their entirety, starting from the top and munching his way to the bottom, core and all.

Lincoln’s affinity for apples — the whole apple — mirrors his pragmatic, waste-not approach to life and leadership.

**

Taken as a whole, this collection of anecdotes about food reveals a man who liked what he liked regardless of his circumstances in life, understood hardship, appreciated the camaraderie that came with sharing meals with soldiers, friends, family, and colleagues, and stayed true to himself.

[1] Accessed 2017.03.09 https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/liho/printVersion.html

[2] Accessed 2017.03.09 https://www.whitehousehistory.org/questions/which-president-started-the-tradition-of-pardoning-the-thanksgiving-turkey

Recipes and content adapted from Abraham Lincoln in the Kitchen: A Culinary Look at his Live and Times. Copyright Rae Katherine Eighmey, 2018, courtesy of Smithsonian Books.