By Zachary Klitzman

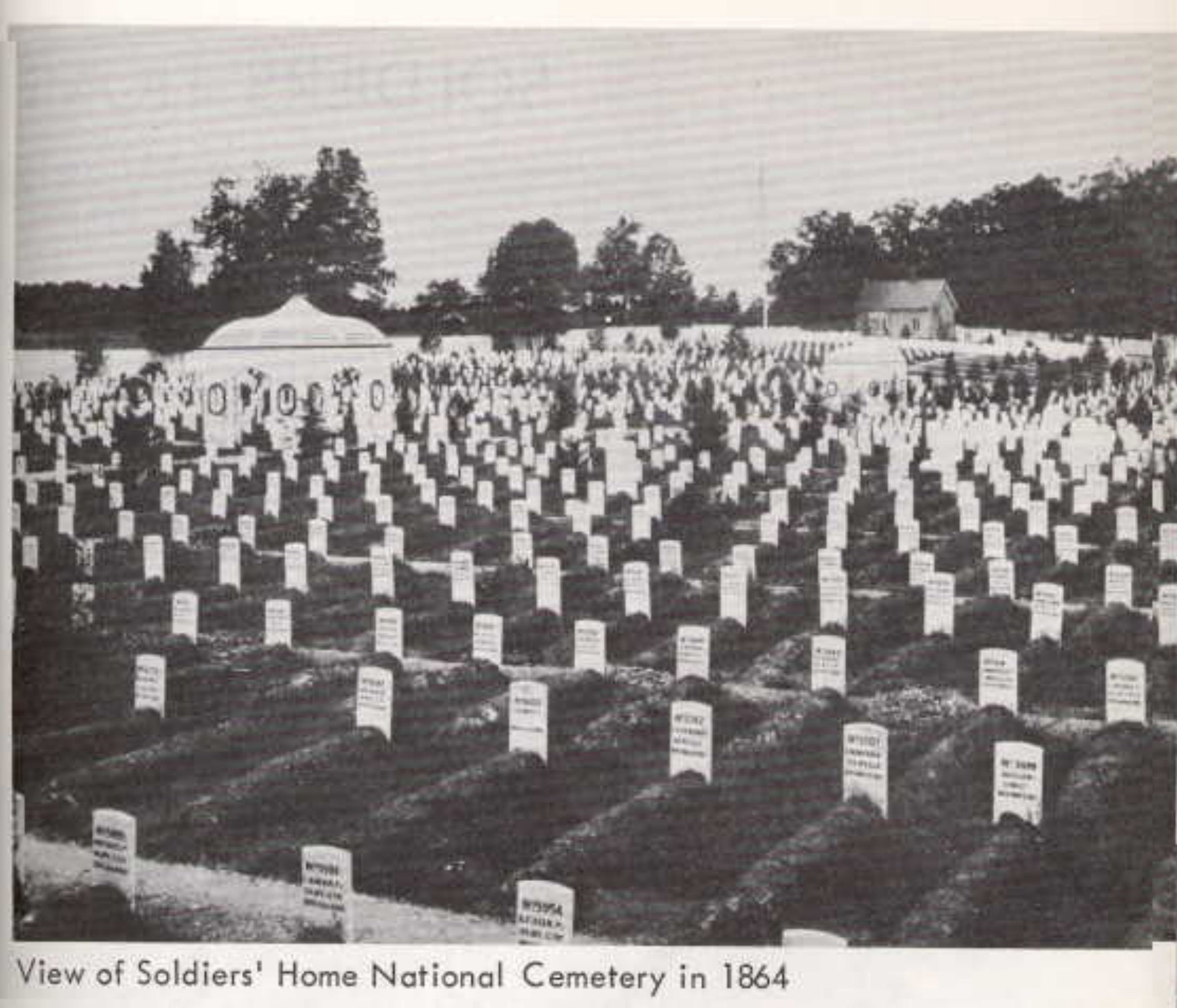

One reason President Lincoln moved to the Cottage was to escape the constant reminders that he encountered at the White House of the ongoing Civil War. But even here at the bucolic Soldiers’ Home, Lincoln could not completely escape the war. Looking just a few hundred yards to the northeast of the Cottage, the President could see the first national cemetery, with dozens of weekly burials.

View of the Soldiers’ Home National Cemetery in 1864.

Opened in August of 1861 in response to the bloodshed of the Battle of Manassas, this cemetery, now officially called the United States Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery, lies adjacent to its namesake retirement home. Although the cemetery is not part of the standard tour at President Lincoln’s Cottage, visitors are welcome to explore the graves on their own.

Such visitors now have a key resource to aid their experience of the cemetery. As part of its Civil War Sesquicentennial celebration, the National Park Service has created a database of the 116 Civil War era national cemeteries scattered throughout the country, and the USSAH National Cemetery is one of the entries. Each selection includes historical context, visitor information, and photos.

In addition to the listings broken down by state, the site has an exhaustive list of additional resources and links, as well as an interactive map showing the location of the burial grounds. Though the majority of the cemeteries are located in states that saw the bulk of the fighting of the Civil War (Virginia has the most with 18 entries), South Dakota, New Mexico, California and Texas are represented.

There are also three short essays: one by Harvard President and historian Drew Gilpin Faust on death in the Civil War (Faust’s 2008 award-winning book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War directly dealt with the unprecedented bloodshed of the war); one by Kelly Merrifield, a contractor with the National Preservation Institute who also wrote some of the site entries, on the evolution of the national cemeteries; and finally an essay by National Cemetery Administration Senior Historian Sara Amy Leach on the erection of the first national cemeteries.

In addition to the Soldiers’ Home cemetery, the database includes two other cemeteries in the District. Battleground National Cemetery, located just a couple of miles from the Cottage off of Georgia Avenue, is one of the smallest national cemeteries in the nation. It serves as the final resting place of 41 Union soldiers who died at the nearby Battle of Fort Stevens. (The Lincolns were forced to evacuate the Cottage in advance of the battle — the only one to take place in the District’s borders — though Abraham Lincoln famously visited the fort during the action.) The other cemetery in the nation’s capital is Congressional Cemetery, which is located in Southeast D.C.

For those interested in the USSAH National Cemetery, President Lincoln’s Cottage has a complete breakdown of the number of burials in the cemetery while Lincoln was living at the Soldiers’ Home. Thanks to the research of a high school American history class in Ohio, the data illustrates that the President could witness an average of eight burials a day from his front door step. The students from Ohio also created a list of the names of the servicemen buried in the cemetery, as well as an analysis of the burials by state and regiment. We also have a guide for how one can find a relative’s grave.