By Cyrus Beschloss, 2014 summer intern at President Lincoln’s Cottage.

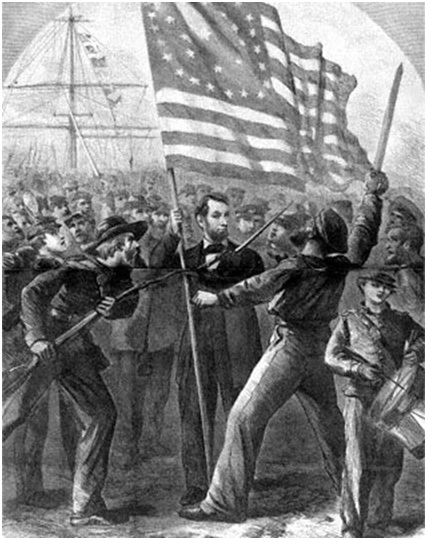

Harper’s Weekly’s depiction of President Lincoln getting involved in the Battle of Fort Stevens (Published October 1st, 1864). Credit: Lehrman Institute. Abraham Lincoln and Soldiers. N.d. N.p.

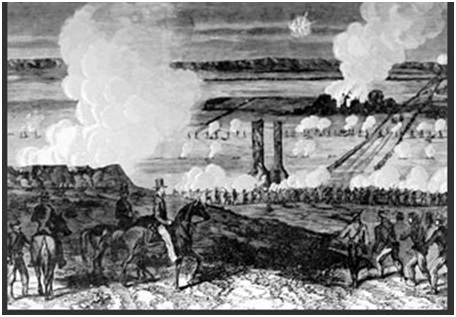

Tomorrow marks the 150th anniversary of the start of the Battle of Fort Stevens, between Union forces led by Generals McCook and Wright, against the Confederates, led by General Early. Fort Stevens, located just 1.5 miles from the Cottage in Washington D.C., was one of 68 forts that surronded the capital, providing defensive support throughout the war. The Battle, which took place from July 11-12, 1864, was the only Civil War battle to take place within the borders of Washington.

Commemorations are underway this week to honor this important moment in Washington history. Here at President Lincoln’s Cottage, the battle is recounted in detail on every tour, as visitors learn how the nearby fighting affected Lincoln and his family. Furthermore, Albert Nelson “A.N.” See’s diary, which is currently on display in the Visitor Education Center, is opened to a page in which See vividly recalls the Battle of Fort Stevens. In addition, the National Park Service—which maintains remnants of Fort Stevens today—has organized events throughout this coming weekend to observe the anniversary, such as a Civil War Historians’ Round Table, hikes through Fort Stevens, music, and, of course, a tribute to honor those who died in the confrontation, at Battleground National Cemetery.

The battle is commemorated for important reasons. It marked a key victory for the Union. As a result of the bravery of the Union soldiers, the national capital avoided falling to the Confederacy. Second, it stands as only the second of two occasions in which an incumbent U.S president stood in harm’s way to witness a battle in the history of the United States (President Madison in the War of 1812 was the first).

Though the Lincoln family had been ordered to leave the Cottage and evacuate to the White House on the night of July 10th, President Lincoln decided to drive out to Fort Stevens in his carriage the next day. He arrived just as the 25th New York Cavalry began its march across the battlefield. As the soldiers marched, both proud and astounded, they cheered, “Hurrah for Lincoln!”[i] Soon, however, Lincoln and his men were exposed to gunfire. A Union surgeon standing next to Lincoln, in fact, was wounded. At this moment, according to legend, someone yelled at the President to “get down, You damn fool!” This quote is most often attributed to future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., though many believe it to be apocryphal.[ii]

President Lincoln arriving on horseback at Fort Stevens (Published by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 13, 1864). Credit: Lincoln at Fort Stevens. N.d. Civil War Traveler, Washington D.C.

President Lincoln arriving on horseback at Fort Stevens (Published by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, August 13, 1864). Credit: Lincoln at Fort Stevens. N.d. Civil War Traveler, Washington D.C.

It did not take long, however, for the ever-vigilant Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, to rush his chief away from the danger. He told the President that if he did not leave, he would order “an ambulance and compel him to go.” The President listened, as he usually did to his Secretary of War, but not without making his feelings on the matter clear. “I thought I was the commander-in-chief,” groaned a frustrated Lincoln.[iii]

This battle does not simply mark a Union victory, or a rare occurrence, with Lincoln’s visit, but it also demonstrates a trend in Lincoln’s behavior: He enjoyed playing with fire. Many times, throughout his presidency, he made himself vulnerable to harm. For instance, although he was often followed by an armed military guard, which was staffed by the New York 11th Calvary then the Union Light Guard from Ohio, he would often ride off to his destination without informing the guard, thus putting himself in danger.

There was even an incident in which he had his famous stovepipe hat shot off from his head while riding his favorite horse, Old Abe, on the grounds of the Cottage. 3 He refused to admit that the shooter had taken aim at him — a demonstration of Lincoln’s immense sense of both trust and naivety. Similarly, his disdain for constant protection from his guard might have contributed to his assassination nine months after the Battle of Fort Stevens. While it is impossible to know if extra precautions would have prevented Booth from shooting Lincoln, it remains clear that Lincoln’s trip to Fort Stevens illustrated a side of the President that is not always depicted. Abraham Lincoln enjoyed adventure, and taking risks. That is why he is remembered today as one of the greatest risk-takers to ever take office, as can be seen by his decisions during critical junctures in the presidency, and by his trip to Fort Stevens on that fateful day in 1864.

[i] Fry, Smith D. “The Fighting Sixth.” The Globe-Republican [Dodge City] 4 Aug. 1893: n. pag. Print.

[ii] Shapell. “Oliver Wendell Holmes Recalls the Incident.” Shapell Manuscript Foundation. American History Online, n.d. Web. 10 July 2014. <http://www.shapell.org/manuscript.aspx?get-down-you-damn-fool-abraham-lincoln-battle-of-fort-stevens>.

[iii] Fry, Smith D. “The Fighting Sixth.” The Globe-Republican [Dodge City] 4 Aug. 1893: n. pag. Print.

View a full list of programs to commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Fort Stevens.