By Cyrus Beschloss, 2014 summer intern at President Lincoln’s Cottage.

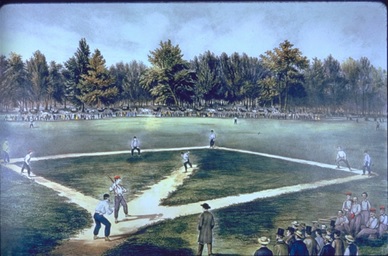

Baseball season is in full swing, and fans across the country feel a distinct buzz in the air as the famed MLB All-Star game approaches. Every year, before each All-Star Game, fans of Major League Baseball reminisce about the captivating yet humble beginnings of the sport. With the All-Star Game just next week, it’s important to look back and recognize the sport’s history in order to fully appreciate the glory of the game that is baseball. Fans often fondly remember General Abner Doubleday, the Union General who is falsely credited as being the architect of the ground rules of Baseball, as we know them today. What might surprise most people, however, is the extent to which one of history’s most monumental figures reveled in the new game. To fully comprehend the significance of President Lincoln attending—and possibly even participating—in baseball games, one must understand the context of the arduous tasks and burdensome challenges he faced at such a critical juncture in this nation’s history.

Baseball season is in full swing, and fans across the country feel a distinct buzz in the air as the famed MLB All-Star game approaches. Every year, before each All-Star Game, fans of Major League Baseball reminisce about the captivating yet humble beginnings of the sport. With the All-Star Game just next week, it’s important to look back and recognize the sport’s history in order to fully appreciate the glory of the game that is baseball. Fans often fondly remember General Abner Doubleday, the Union General who is falsely credited as being the architect of the ground rules of Baseball, as we know them today. What might surprise most people, however, is the extent to which one of history’s most monumental figures reveled in the new game. To fully comprehend the significance of President Lincoln attending—and possibly even participating—in baseball games, one must understand the context of the arduous tasks and burdensome challenges he faced at such a critical juncture in this nation’s history.

Lincoln is often acknowledged as the first president to have been fond of Baseball. There are records which suggest that Lincoln played the sport. On what would have been President Lincoln’s 111th birthday, the Ottawa (Illinois) Herald published an article regarding different aspects of Lincoln’s personal life[i]. Not only did the article confirm that “He would leave his [Springfield law] office any time of the day,” but it also added “He left the courtroom to engage in a game of ball.”

A more unsung example of Lincoln’s love for baseball comes from a 1914 article from the Chicago Eagle, in which the author interviews Winfield Scott Larner, who recounts his experience of watching a baseball game between the Quartermaster’s Department and the Commissary Department in the summer of 1862, only to be joined by the Commander-in-Chief — so Larner says. The President arrived in the “well-known black carriage drawn by two black horses.” He then dismounted from the carriage, and while taking the hand of his son, Tad, made his way over to the stands. He and Tad sat “unobtrusively, and unseen by the crowd.” They arrived at the start of the game, and stayed until the close[ii].

A more unsung example of Lincoln’s love for baseball comes from a 1914 article from the Chicago Eagle, in which the author interviews Winfield Scott Larner, who recounts his experience of watching a baseball game between the Quartermaster’s Department and the Commissary Department in the summer of 1862, only to be joined by the Commander-in-Chief — so Larner says. The President arrived in the “well-known black carriage drawn by two black horses.” He then dismounted from the carriage, and while taking the hand of his son, Tad, made his way over to the stands. He and Tad sat “unobtrusively, and unseen by the crowd.” They arrived at the start of the game, and stayed until the close[ii].

Afterwards, according to the story, if we can believe it, the president watched as each team gave the other three cheers to mark the end of the game; a custom that is unfortunately no longer practiced. After “Lincoln took off his hat and joined in on the cheering,” he was recognized, at which point a player called for “Three cheers for Old Abe.” Naturally, three cheers were passionately given by the stunned crowd and players.

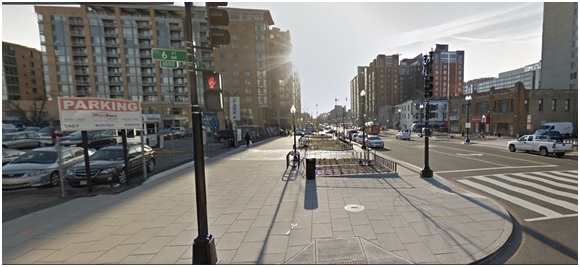

Above is a current view of the corner between 6thStreet, and K Street NW in Washington D.C., where the game was said to have taken place. While it lacks its former glory, it clearly received, at least on some days, much sunlight (or at least it did when there were not 14-story buildings in the way). Its location is slightly east of the White House, in the general direction of the Lincoln’s summer residence at the Soldiers’ Home. Based on such a location, it is not hard to believe that he might have stopped by the field on his way home from work, hoping to see some action.

Above is a current view of the corner between 6thStreet, and K Street NW in Washington D.C., where the game was said to have taken place. While it lacks its former glory, it clearly received, at least on some days, much sunlight (or at least it did when there were not 14-story buildings in the way). Its location is slightly east of the White House, in the general direction of the Lincoln’s summer residence at the Soldiers’ Home. Based on such a location, it is not hard to believe that he might have stopped by the field on his way home from work, hoping to see some action.

Looking back at such an event, it is easy to fail to recognize the pressing issues the President had to attend to at the time. Yet, the game took place in the summer of 1862, in the midst of some of his biggest decisions and actions as President: On May 20he signed the Homestead Act; on June 19, he signed legislation to end all present, and future slavery in the Western Territories; on July 1 he signed the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 and the Revenue Act of 1862; from August 28-30, Confederate troops defeat the Union Army in the 2nd Battle of Bull Run, forcing the Union troops to retreat to Washington DC, as the Civil War furiously rages on; on September 25, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus throughout the U.S.; and three days before, on September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation while living at the Cottage.

Clearly, baseball was important to Lincoln. Otherwise, it would seem odd for a president to stop working for several hours, in a period of great strife in his country, unless he truly felt that what he was doing would be helpful to him. Maybe baseball provided him with a way to release stress, and take a step back from the chaos ensuing around him. Maybe he felt that watching baseball was a good way to bond with his son, who most likely felt ignored by his overwhelmed father. All that is clear is that on that day in 1862, old Abe Lincoln felt compelled to take several hours to marvel at a game that has since become the nation’s pastime.

***

Source for top photo: The American National Game of Baseball. The World Series of 1862. N.d. Into the Marchand Archive. Web. 07 July 2014. <http://marchand.historyproject.ucdavis.edu/author/lkraus/>.

Source for middle photo: Lindquist, Travis. 2009. St Louis. 2009 MLB All-Star Game. Web. 07 July 2014. <http://archive.azcentral.com/closeup/articles/0714spt-closeupallstar-CR.html>.

Source for lower photo: Google Street View. Web. 07 July 2014. <https://www.google.com/maps/@38.902662,-77.019894,3a,75y,92.49h,82.79t/data=!3m4!1e1!3m2!1s5WV8fcyT9boE3vUjdwx_sw!2e0>.

[i] Rothschild, Richard. “Lincoln Was Game for Baseball.” Chicago Tribune. N.p., 11 Feb. 2003. Web. 07 July 2014. <http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2003-02-11/sports/0302110160_1_16th-president-historian-jules-tygiel-abner-doubleday>.

[ii] “Was a Baseball Fan.” The Chicago Eagle [Chicago] 6 June 1914: n. pag 2. Print.