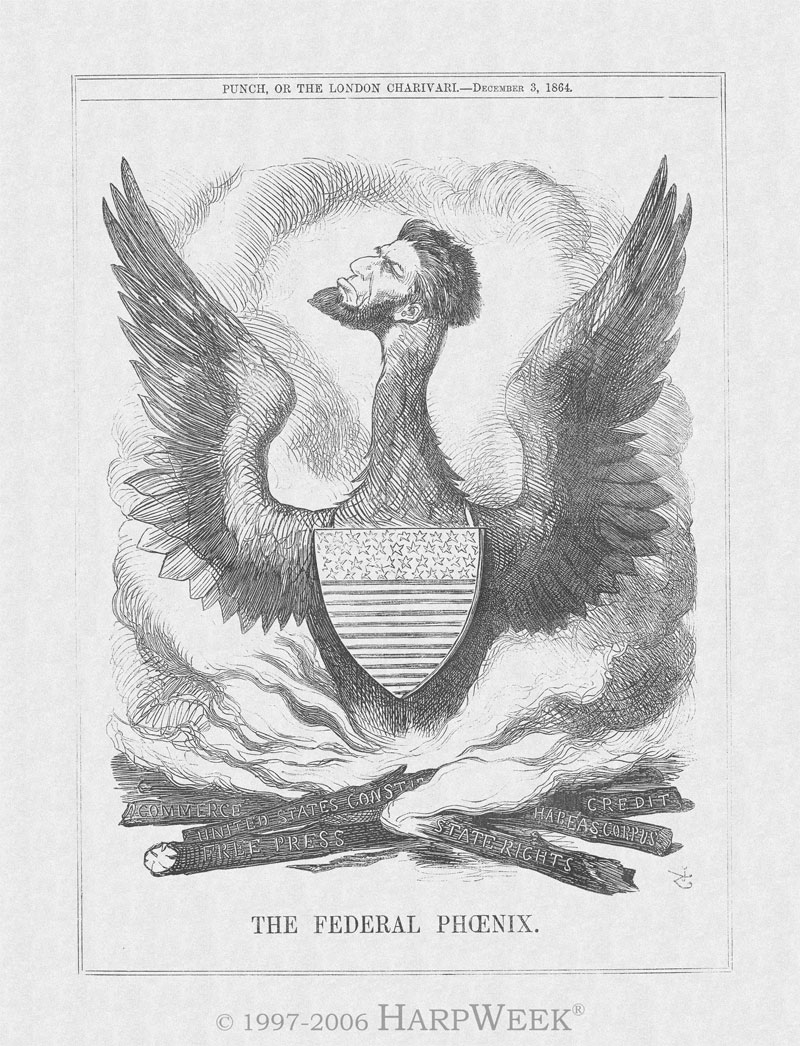

In this 1864 cartoon, Lincoln is mockingly portrayed as a “Federal Phoenix” rising up from the ashes of burnt logs “United States Constitution,” “Commerce,” “Free Press,” “States Rights,” “Credit” and “Habeas Corpus.”

By Eve Errickson

Visitors to the Cottage last summer may have been surprised by the presence of Mr. Quick — a resident of the Armed Forces Retirement Home — on the grounds, distributing flyers that voice his protest of practices at the Home. While President Lincoln’s Cottage is a historic site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and has separate management from the Armed Forces Retirement Home, we recognize his First Amendment rights to present his views peacefully on the grounds of the Cottage. As the First Amendment declares: “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press or of the right to peaceably assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Mr. Quick’s exercise of his rights inspired our staff to take a fresh look at the legal debate over President Lincoln’s actions to suppress the free speech of journalists and other private citizens who objected to the Civil War. His actions brought to light a complex intersection of laws which include the First Amendment and due process issues. In 1861, mob violence throughout the Union forced the closure of newspapers that published editorials opposing war between the states and targeted the writers themselves for public humiliations. In response, Lincoln focused exclusively on quick, regional stabilization — “without ruinous waste of time.”[i] The Union Army confiscated, monitored and censored communications sent via the mail and wire, including newspapers. Journalists and newspaper owners who persisted after government suppression were arrested and held without warrants or due process of law.

The suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in April 1861 was initially directed at quelling unrest in Maryland. In February 1862, Lincoln ordered the release of political and state prisoners once “The line between loyalty and disloyalty [was] plainly defined,” only to suspend the writ again and extended throughout the Union in 1862. Congress confirmed the suspension, after the fact, through passage of the Habeas Corpus Act in 1863.[ii] Prison records reflect that as many as 4,000 civilians were imprisoned as part of efforts to suppress anti-war sentiment—including politicians, foreign nationals, and diplomats. According to historian Mark Neely, Jr.:

The government thus unleashed every dogberry across the nation to make loosely defined arrests whose victims had no remedy to appeal to judges for writs of habeas corpus and might be essentially tried by court martial.[iii]

The intersection of the war and the suppression of free speech have invoked a wide variety of interpretations. As historian Akhil Reed Amar has observed, Lincoln focused on the preservation of the Union. For Lincoln, the Constitution was an expression of statehood, rather than an expression of individual rights, and saw no contradiction in trying to preserve a democratic union by force: “Continue to execute all the express provisions of our national Constitution, and the Union will endure forever” he said in his first inaugural address. [iv] Others cite the absence of legal precedent and the importance of public safety—in essence, Lincoln believed that his actions were necessary to minimize the rebellion, even at the cost of essential American civil liberties and innocent lives.[v] Whether or not his understanding of Constitutional issues was grounded in good faith or indifference to civil rights is a continuing and robust debate among lawyers and historians alike.

Continue the article HERE.

Ms. Errickson is an attorney and Director of Contracts at the National Trust For Historic Preservation.

[i] A Lincoln “Letter to Erastus Corning and Others” June 12, 1863, http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=612.

[ii] Mark Neely Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991) p. 69.

[iii] Mark Neely Jr., Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America: The Last Best Hope of Earth (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993) p. 126.

[iv] Akhil Reed Amar, “Abraham Lincoln and the American Union” Yale Faculty Scholarship Series, Paper 854, (2001), p. 111 http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/854 citing Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address.

[v] Dean Sprague, Freedom Under Lincoln (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965) p. 302; Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, his agenda and an unnecessary war (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2002) p. 159.