By Zach Klitzman

Perhaps it’s fate that this week’s election has been so hotly contested. Four days after the midterms will mark the 150th anniversary of the Presidential Election of 1860, which saw the second highest voter turnout in American history (81.2% of eligible voters). Abraham Lincoln won the intense election, angering Southern slave owners who in turn seceded. As poet Walt Whitman wrote in “Year of Meteors,” 1860 with its influential election was a “year all mottled with evil and good! [A] year of forebodings!”

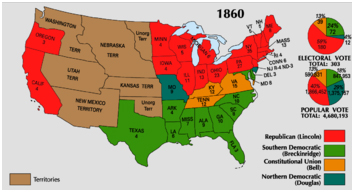

The infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857 and John Brown’s raid in 1859 both increased sectional tension between the Northern Free States and the Southern Slave States during the late 1850s. As a result, the political landscape fragmented in 1860, with four candidates running for President. The Democratic Party — which had occupied the White House for all but eight of the previous 32 years — split into a Southern and Northern wing, nominating Vice President John Breckinridge and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, respectively. The new Constitutional Union Party nominated former Tennessee Senator John Bell with the slogan “the Union as it is, and the Constitution as it is.” Last was Lincoln, the nascent Republican Party’s candidate, whose previous top elected office was as a one-term Representative from Illinois over 10 years previously.

Bolstered by his moderate but firm stance on slavery, as well as national exposure from debating Douglas for the Illinois Senate seat in 1858, Lincoln won the Republican nomination in 1860. He upset three more established politicians: New York Senator William Seward, Ohio Senator Salmon Chase and former Missouri Representative Edward Bates. By comparison to Lincoln, Seward was too radical, Chase too connected to the Democrats and Bates too old. So instead, Lincoln won the nomination. (He eventually nominated Seward, Chase and Bates to serve as members of his cabinet, and they all would advise him on the Emancipation Proclamation.)

As was common practice, Lincoln did not personally campaign. Instead, Republican organizers throughout the North campaigned on his behalf, energizing the base with their arguments against the expansion of slavery. They campaigned only sparingly in the Border States and not at all in the South. In fact Lincoln’s name did not even appear on the ballot in 10 of the 11 states that eventually seceded, and he only won 1.1% of the vote in the eleventh state, Virginia.

This focus on the Northern states succeeded. Douglas tried playing both sides but instead just alienated them. Bell was a non-factor, carrying just three Upper South states. And while Breckinridge carried the rest of the South, his 72 electoral votes were not enough. Lincoln won all but three of the electoral votes in the Free States, and despite winning just 39.8% of the popular vote–the smallest plurality a President has ever earned—he won a majority of 180 out of 303 electoral votes, guaranteeing his election. Though divided opposition bolstered his electoral votes, if had faced just a single opponent he would have won the Electoral College 169-134.

Southerners equated Lincoln’s opposition to the expansion of slavery with outright abolition. Without new Slave states in the west to balance new Free states, they argued, the balance of power in Congress would soon shift to the Free States. Furthermore, Lincoln’s election without a single Southern electoral vote did not bode well. If the Northerners did not need Southern support for victory, what incentive would they have to compromise? With this in mind, seven states acted preemptively, and seceded by the time Lincoln was inaugurated in March 1861. Following the attack on Fort Sumter, another four would do so as well.

Lincoln’s election had made the Civil War inevitable.