By Curtis Harris

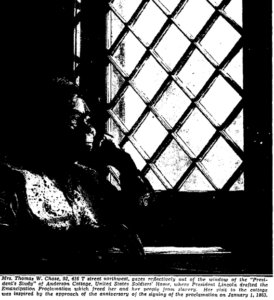

On a late December day in 1936, Anna Harrison Chase walked from her home near Logan Circle to the Soldiers’ Home. The longtime Washington resident was intent on visiting the place where President Abraham Lincoln had deliberated and constructed the Emancipation Proclamation. Her pilgrimage that winter day was one of many arduous journeys in Chase’s life. Born on a plantation in Caroline County, Virginia, she seized her freedom during the Civil War with the aid of the United States Army. Traveling by train from the nearby town of Fredericksburg, she arrived in the District of Columbia in 1862. In the nation’s capital Anna Harrison endured life at a contraband camp, married Thomas W. Chase – himself a recently freed man from Maryland – and began a family that accomplished much from their enslaved beginnings becoming professionals, government employees, and servicemen in the U.S. military.

The Chase family’s journey – literal and symbolic – leads to many important questions on the Civil War experience and its aftermath for African Americans in D.C. and across the United States. How did black Americans, particularly those freed from slavery, remember their wartime experience? What meaning did they ascribe to the war and their resulting freedom?

WAR and EMANCIPATION

Anna Harrison was born in 1844 just as American society and politics were increasingly fracturing over the issue of slavery. Obviously, the subject had long been a sore point in American history. From the colonial era and the Revolution into the constitutional debates and Missouri Compromise, slavery had always been a rancorous issue. However, the 1840s and 1850s saw the rise of political parties devoted centrally to opposing slavery.

A decade-and-a-half after Chase’s birth, the nation plunged into civil war over the status of slavery and enslaved persons like herself. Much like the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, enslaved Virginians aided the enemies of their captors. Furthermore, Virginians like Chase propelled the federal government to enact permanent and immediate emancipation by 1865. Although not completely in lockstep, the alliance of enslaved Americans in the South and white Americans opposed to slavery and/or secession proved durable enough to win the Civil War.

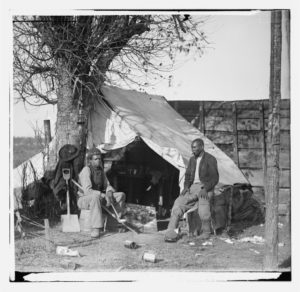

As federal troops moved further into Virginia to suppress the rebellion, more and more “contrabands” found their way into Union lines. With their erstwhile masters on the run, or killed, many enslaved Virginians broke out of their generational bondage by escaping to Washington, D.C. The city was the best option for permanent freedom, particularly after the passage of an emancipation act for the federal city in April 1862. Chase herself spoke to the advantageous nature that Civil War chaos created for black freedom in the spring of 1862 when she made her bid for freedom:

“Our old master and missus were dead, and we heard that our young master had been killed in the war,” related Mrs. Chase. “So we hitched up the ox cart and I led my family away to the Free State.” The “Free State” Mrs. Chase explained meant to the slaves all of the territory inside the lines of the Union Army. By ox cart her family went to Fredericksburg, Va., where they boarded a train for Washington.[1]

Anna’s recollection of escape seems rather quotidian and blasé. There was no harrowing excursion into a forest or maroon experience in a swamp. No violent resistance to an overseer or fending off bloodhounds. Perhaps there was, but she didn’t mention any dramatic obstacle. She and her family simply walked off the plantation in Caroline County, Virginia, and caught a train to freedom.

Despite her nonchalant retelling, it is wise for us today to consider that this was an incredible act of bravery. Just because this particular escape went off without a hitch, didn’t mean the threat of violence didn’t hang in the air and that many other enslaved Americans had their plans foiled and were punished for trying to “steal themselves.” Even in securing freedom by reaching Washington, the travails of the Civil War weren’t over for freedpeople like Chase.

Although Chase does not describe in great detail her Civil War experience in D.C., she did describe Washington as “just a mudhole then.” The situation in the nation’s capital, as well as other sites of refuge, was dire for the formerly enslaved. The District held a special danger with neighboring Maryland not abolishing slavery until the fall of 1864. This meant that people who had been enslaved in that state but fled for the District were always liable for recapture. Anna had protection against that danger given her escape from a rebellious state, but her future husband Thomas Chase had escaped from Annapolis, Maryland, and thus could be subject to capture and return.

Potential re-enslavement aside, other dangers lurked in the physical environment of Civil War America.[2] A son of president Abraham Lincoln died of typhoid fever, a disease spread by contaminated water. If the commander-in-chief’s family was devastated by such unsanitary conditions, surely the freedmen and freedwomen of the contraband, or refugee, camps might prove even more susceptible. Mary Lincoln described the dire situation of the camps to her husband:

[Seamstress Elizabeth Keckley] says the immense number of contrabands in W[ashington] are suffering intensely, many without bed covering & having to use any bits of clothing to cover themselves. Many dying of want….[3]

The attention the Lincolns gave to emancipated people was reciprocated. Anna Chase recalled in her Washington Post interview that she would see the president daily commuting from his summer residence at the Soldiers’ Home to the White House in 1862. Meanwhile, Mary Dines, another freedwoman, recalled the president and first lady visiting her refugee camp and singing with the assembled contrabands.[4]

Despite the miserable conditions, the freedpeople went to work (or as Mrs. Chase phrased it, “I went into service”) providing direct and indirect aid to the Union war effort as laborers, nurses, spies, and soldiers. The material aid and comfort provided by black Americans and the Union military for each other was ably summarized by historian Chandra Manning: “The army and refugees from slavery, then, did not need exactly the same things, but they knew they needed each other, and so they built a tenuous alliance.” This alliance, Manning argued, created the groundwork for eventual citizenship for all black Americans that began during the war as military exigency, but was codified afterwards via constitutional amendment.[5]

The “Free State” created by the work of black Americans alongside Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, D.C. emancipation, Maryland’s abolition of slavery, the Thirteenth Amendment’s ratification to the U.S. Constitution, and the federal army’s punishing pressure left the slave system bloodied and finally beaten in the waning months of 1865. This deliverance from slavery’s evils to citizenship’s protections was a long time coming from the vantage point of black Americans. As Anna and Thomas married in 1868, they, like all Americans, had to wonder what the future held for the country in the aftermath of slavery.

LIFE AND MEMORY AFTER THE WAR

How was life to go on for black and white Americans without the script of slavery to go by? Intriguingly, how would the races remember the war? If all Americans could agree that the war was indeed about slavery, that the end of slavery was a triumph for human rights and the nation, and that freedom and equal was a glorious outcome, things would bode well for folk like Anna and Thomas Chase.

This was not the narrative nor memory everybody shared after the war. In the white South, the Lost Cause triumphed as the dominant narrative by 1900. This memory of the Civil War sought to introduce a racial script as close to slavery as possible for whites and blacks to live by. So compelling was the Lost Cause that white Northerners largely bought into the memory as well. By sidelining and silencing black Americans, white Americans could reconcile the Civil War as a brotherly quarrel that, although regrettable, had showcased each side’s bravery in combat. Any discussion of the ideological stakes concerning freedom and slavery were mentally walled off. No surprise then that this was also the era that segregation and Jim Crow laws flourished with the acquiescence of the federal court system. The Chase family – like most black Americans – did not buy into the Lost Cause. As many of them knew from personal experience, the Civil War meant the demise of their enslavement; their enfranchisement as voters; and their confirmation as American citizens.

Iconography and symbols of the Lost Cause, which white Northerners and Southerners alike promulgated in the decades after the Civil War

Anna and Thomas could speak to the war’s very real deliverance of political and social freedom. So could their eight children: Joseph (b. 1866), Jonathan (b. 1869), Susan (b. 1873), Louis (b. 1875), Fanny (b. 1878), Charles (b. 1880), William (b. 1885), and Isabella (b. 1887).[6] Had the Civil War not occurred, the progeny of Anna and Thomas would have been enslaved just like the vast majority African Americans over the previous two hundred years. More than simply being free, though, Anna proudly noted her family’s success in the post-war period: “Mr. Chase graduated from Howard University with a law degree later. Oh, I’ve watched my people and my children and grandchildren become lawyers, doctors, musicians and teachers.”

Anna herself exemplified the expanding horizons. Throughout the federal census records consulted, she was consistently listed after the war as either employed at home or as a domestic worker. That she was listed at all was an affront to the slave system. Prior to the Civil War, the federal census only listed enslaved black persons as property owned by a white person. Her name being recorded in 1870 and beyond was itself another victory of the war. More importantly, though, in the 1870, 1880, 1900 and 1910 federal censuses it was noted she could neither read nor write. However, in the 1920 federal census, Anna Chase was noted as finally having those abilities, never too old to learn or defy racism. All the Chase children recorded by the census were said to be literate, thus taking advantage of the public schools established for black children in Washington during Reconstruction. Their father, up until his death in 1905, worked as a lawyer thus showing his own mastery of the written word despite the marginal-at-best education provided to the enslaved prior to the Civil War. [7]

With so many children, the Chases would also be grandparents many times over. At least three of their grandsons would serve in the United States military. Most notable was the career of Hyman Yates Chase. Hyman earned a doctoral degree from Stanford University and became one of the few black Army officers during World War II and the Korean War. Hyman and his wife, Nelka, were buried in Arlington National Cemetery in 1983 and 1996, respectively.

Anna’s experience of seeing her family succeed inspired a faith that their success – indeed the success of African Americans – would continue apace. However, that social climb needed firm grounding in the historical roots of slavery. Keeping alive the memory of bondage’s depravations and the blessing of freedom sharpened the accomplishments made by the Chases and African Americans generally. Particularly in the face of continuing segregation, these achievements were not to be taken for granted.

After telling her story to the Post, Anna Chase returned to her R Street home near Logan Circle. There, she made sure to inform her great-granddaughter of the enslaved experience. Unfortunately, we do not know how much of that wisdom imparted from Anna remained with her young descendent. Such is the question anytime an elder seeks to impart knowledge on a younger generation. What’s undoubtable is that Anna felt a determination to imprint as much of her life experience – and the experience at-large of those who had been slaves – upon those who did not live through slavery’s horrors. Indeed, Mrs. Chase directly addressed the idea that it would better to forget or remain silent about slavery, a favorite amnesia of the Lost Cause.

“Now they tell me I should not talk so much about the days when I was a slave,” Mrs. Chase opined. “But I can truly tell you of those days.” She spoke of seeing family members shackled and sold, others lashed and shot. “I know what slavery was,” the 96-year old woman relayed. “It was not our fault that we were held down.” Then, Chase pivoted dramatically to the present and future: “I’m proud to see my people rising.”

WHAT’S TO COME

Tracking down information on Anna Harrison Chase and her family was no easy task nor is it complete by any means. The sketches of her life, and that of her family, have been largely compiled thanks to information from that single Washington Post article in 1936; information from the United States federal government, particularly the census and military service records; and vital records from the District of Columbia. Compared to Abraham Lincoln, this level of information is paltry. Yet, millions of other Americans liberated from bondage never had a chance to record their story for posterity.

In my own family history, I have been able to identify 11 ancestors who were emancipated during the Civil War. Unfortunately, all I have of their lives are names alongside basic information such as state of birth and occupation. None of them had the opportunity to sit down with a major newspaper and tell their story. Compared to these persons, the information we have on Anna Chase is a treasure trove.

Using those primary documents, alongside research of historians, religious scholars, and architects, Mrs. Chase’s life becomes a vehicle for enlightenment on the important questions of memory, emancipation, and indeed pilgrimage. Mrs. Chase sought out the Cottage because of its special role in the Emancipation Proclamation’s development.

Still, we have much to learn of the woman who has inspired many questions and new thoughts among the staff at President Lincoln’s Cottage. We are actively seeking living descendants of Anna Chase in hopes of finding out more of their family history. In the meantime, we suggest that you all take time this holiday season to ponder, uncover, and record your own family history. At the very least, your descendants will thank you for it. And maybe even some museum down the line will too.

Curtis Harris is a doctoral history student at American University. He worked at President Lincoln’s Cottage for seven years, as a Museum Program Associate and as Marketing & Membership Coordinator.

[1] This quote, and all others attributed from Anna Harrison Chase in this article, are from James J. Cullinane, “Mrs. Thomas Chase Visits House Where Lincoln Wrote Act,” Washington Post, December 27, 1936, pg. M5.

[2] Jim Downs’s Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction; Chandra Manning’s Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War; and Brian Steel Wills’s Inglorious Passages: Noncombatant Deaths in the American Civil War all excellently show the perils that Americans faced during the Civil War, even those who were not fighting in the battles.

[3] “Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 2. General Correspondence. 1858-1864: Mary Todd Lincoln to Abraham Lincoln, [November 3, 1862] (Money to purchase clothes for contrabands; endorsed by Mrs. Lincoln on envelope),” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mal4238700/.

[4] Matthew Pinsker, Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers’ Home (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 16.

[5] Chandra Manning, Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 8.

[6] Information gathered from the 1870, 1880, and 1900 United States Census via ancestry.com. Births may be off by one year due to census records not specifying exact birthdate, only the age of the child the year the census was tabulated.

[7] Anna Chase’s claim that Thomas graduated from Howard University with a law degree could not be verified. However, Thomas Chase was listed in several Washington city directories between 1893 and 1904 as a lawyer. His occupation as a lawyer was also noted in the federal census. Wherever or however he obtained a law degree or license, it is apparent that Mr. Chase practiced law as his vocation.