Arkansas Resolutions: “Compromise” on the Eve of the Civil War

by Curtis Harris

With each Civil War anniversary, public debate on the cause and meaning of the war as well as the meaning and outcomes of Reconstruction is reinvigorated. That debate has often centered on how we choose to memorialize the war, including who should be memorialized. In October 2017, White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, in an interview with Fox News, ruminated on the removal of Confederate statues. Kelly’s response shifted popular debate from memorialization to causation of the war:

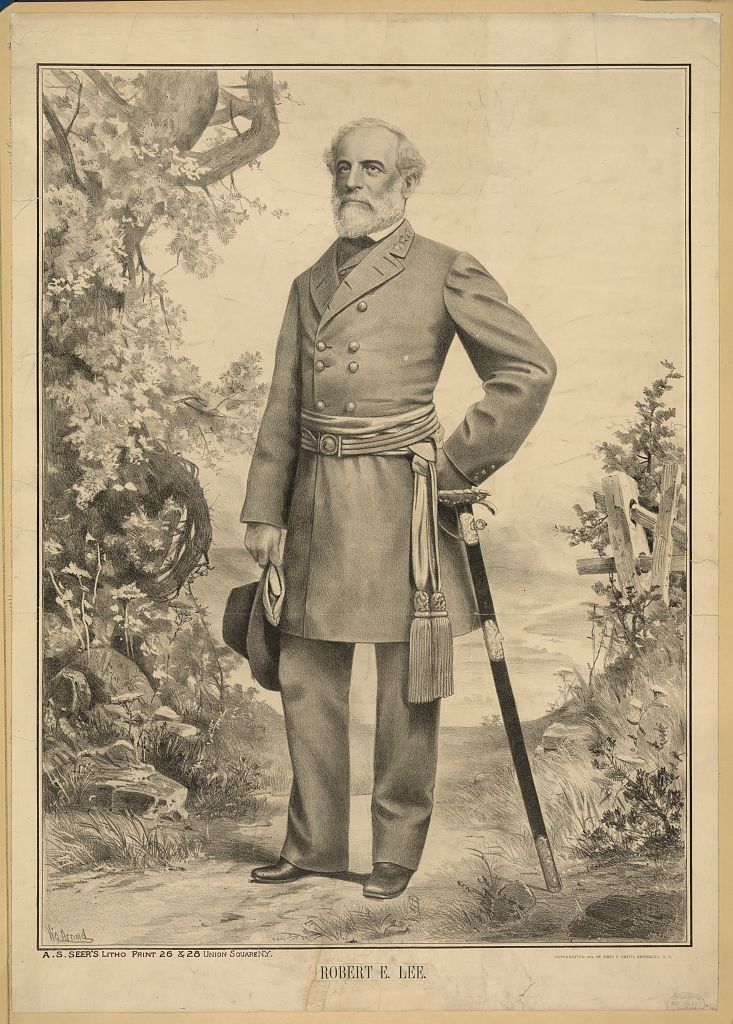

“I would tell you that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man,” Kelly said. “He was a man that gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country. It was always loyalty to state first back in those days. Now it’s different today. But the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War, and men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand where their conscience had them make their stand.”

Robert E. Lee, Library of Congress

Kelly’s statements drew criticism from prominent Civil War and Reconstruction historians and storied organizations such as the American Historical Association. In addition to those professional historians, the general public also took notice of the comments. Indeed, when a prominent person makes claims about Lincoln or the Civil War, their statements routinely inspire questions from visitors on tours of President Lincoln’s Cottage. In Kelly’s case, his comments concerning “loyalty to state first” and “compromise” have been a constant theme of questions over the years that I have given tours at the Cottage. Since the topics arise on tours often and clearly were on the mind of a prominent government official, I think it is important to assess the notions of loyalty and compromise relating to the Civil War and slavery.

Specifically, what did loyalty mean with regards to state, country, and Union? Did every American reflexively choose state over country, no matter their personal ideological convictions? What did compromise look like for those who eventually chose state over country?

LACK OF COMPROMISE?

The historical record shows that there was a keen eagerness by mainstream politicians to compromise on slavery prior to the Civil War. For example, the grand bargain during the Constitutional Convention concerning representation in the legislative branch hinged on slavery. Writing in the third-person, slaveowner James Madison at the convention confided: “But he contended that the States were divided into different interests not by their difference of size, but by other circumstances; the most material of which resulted partly from climate, but principally from the effects of their having or not having slaves.”

This insight drove Madison to urge the creation of two chambers of Congress, one based on population that would include three-fifths of the enslaved (the House of Representatives) and one devoid of such considerations (the Senate). This compromise helped ensure an electoral advantage to slave states that helped elevate several slaveholders as president. Eight of our first twelve presidents owned other humans while they executed the duties of the presidency. Meanwhile, other presidents, such as Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, carried out the political wishes of the slave interest by lobbying for the annexation of Cuba or promoting the admission of Kansas as a slave state, respectively.

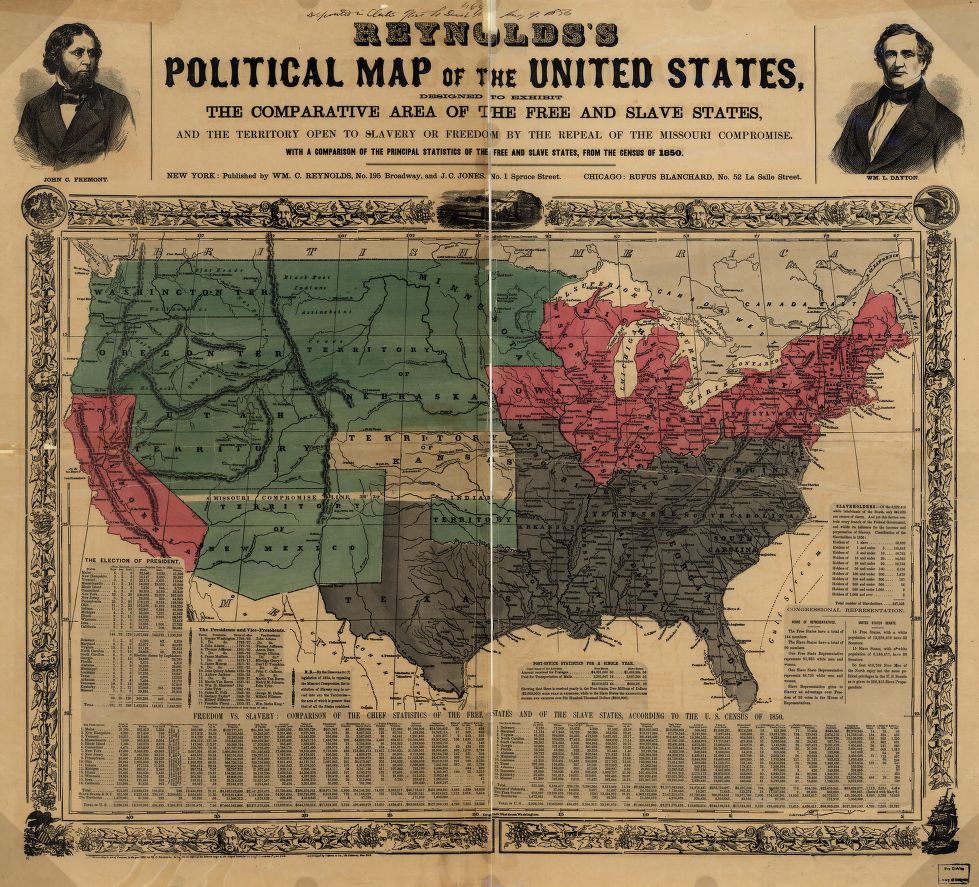

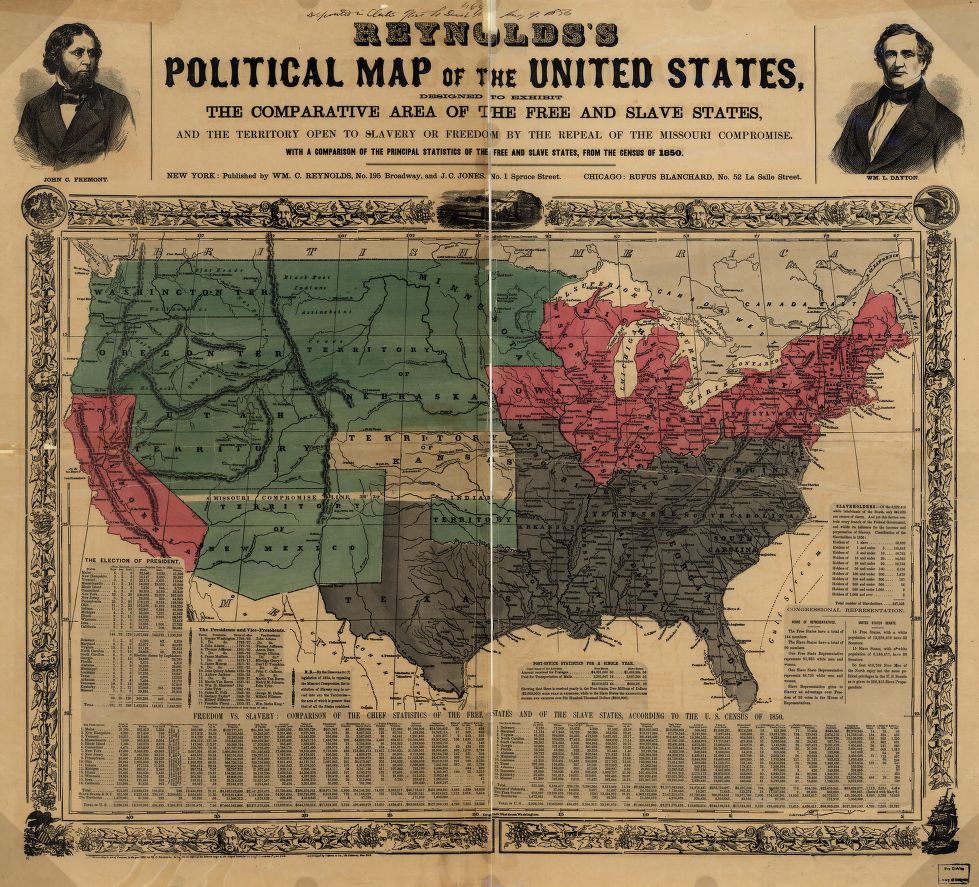

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 exemplified the continued desire and commitment to compromise on slavery.

Reynolds’s political map of the United States, designed to exhibit the comparative area of the free and slave states and the territory open to slavery or freedom by the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. (Library of Congress, 1856)

Instead of satisfying all sides on the issue of slavery, though, the institution’s bedrock was strengthened through these compromises while anti-slavery advocates grew more strident organizing parties such as the Liberty Party and the Free Soil Party before coalescing into the Republican Party in the mid-1850s.

The antebellum compromises, however, proved inadequate to quell forever the festering sore of human bondage in a nation ostensibly conceived in liberty. Indeed, one last compromising gambit was proposed during the winter of 1860 and 1861 supported, by outgoing President Buchanan. Passing Congress on March 2, 1861, a proposed 13th Amendment, popularly known as the Corwin Amendment, stated:

“No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.”

Abraham Lincoln, despite well-known and unflinching anti-slavery sentiment, assented to this amendment in his First Inaugural Address hoping to stave off civil war. For the incoming president, however, he would countenance no expansion of slavery a departure from previous administrations that viewed the geographic extension of slavery and human misery as perfectly normal topic of compromise.

Nonetheless, slavery hardliners and abolitionists denounced the measure for opposing ideological reasons. The amendment did not guarantee slavery’s extension into the territories, hence it was considered a pitiful gesture for the pro-slavery forces, who contended slave-based societies were the highest form of civilization. Meanwhile, the acknowledgement, however euphemistically, of slavery’s unfettered existence within the current slave states was anathema to abolitionists.

By this point, the Deep South had organized itself as the Confederate States of America. Their ordinances of secession explicitly and repeatedly stated that the restriction of slavery to its current limits was unfair and draconian. Here it is important to remember that the United States was the only society in the Western Hemisphere expanding the limits of slavery during the nineteenth century. For the newly-minted Confederacy, they desired a continuation of a beneficial institution built on the inequality of the races. That ideology was threatened by the Republican insistence that all men were created equal.

As Henry Benning of Georgia phrased it in his February 1861 plea urging Virginia to secede, “By the time the North shall have attained the power, the black race will be in a large majority, and then we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything…. We will be completely exterminated, and the land will be left in the possession of the blacks, and then it will go back into a wilderness and become another Africa or Santo Domingo [Haiti].”

Benning’s appeal to Virginia summed up the dilemma for the other Upper South states of Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri. Waffling throughout February, March and April of 1861, these states’ political classes neither embraced secession nor the incoming Lincoln administration and its threat to slavery and racial inequality.

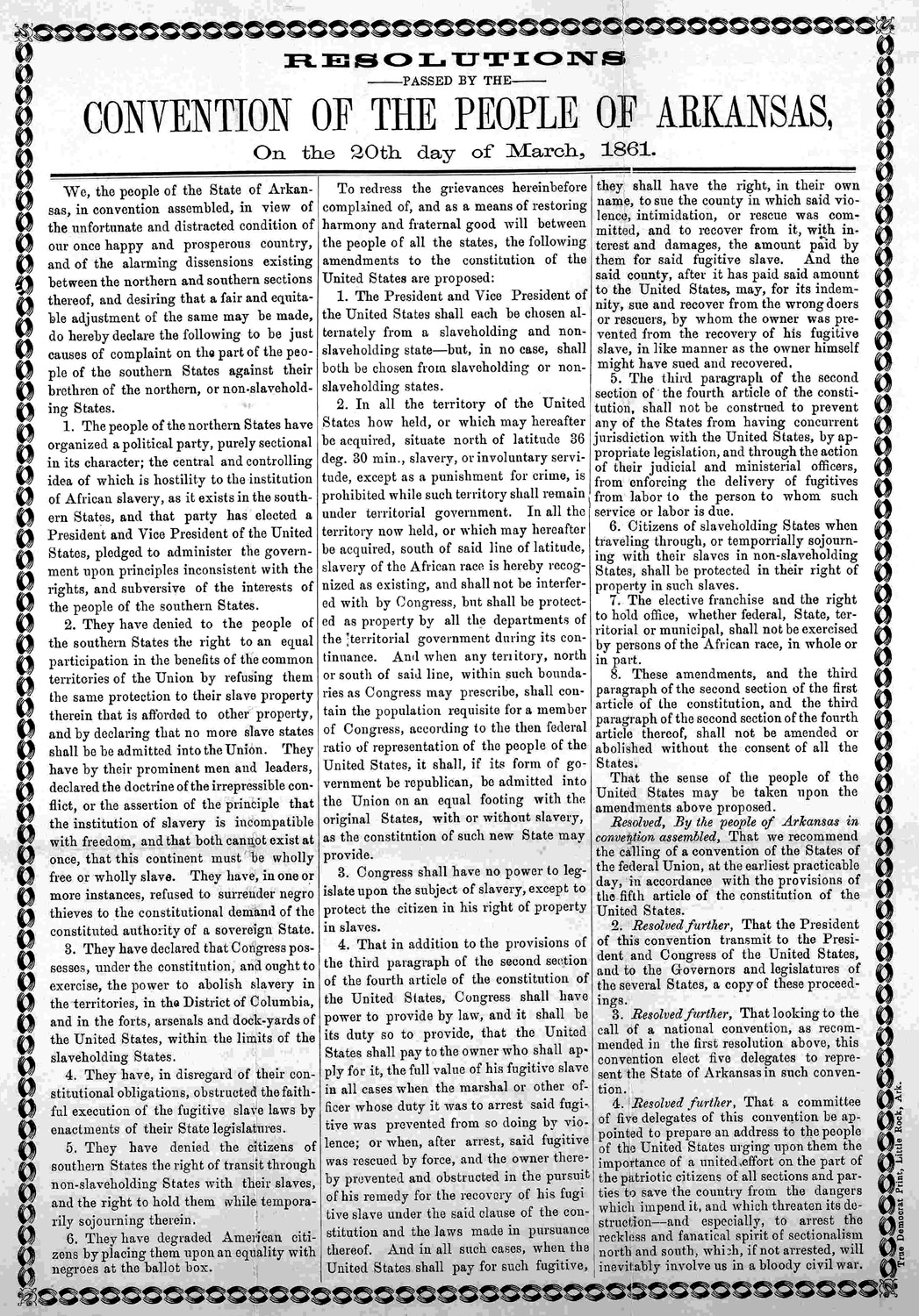

Arkansas’s secession convention merits special notice among these undecideds. Before Arkansas’s state government cast its lot with the Confederacy in May 1861, its convention delivered a package of proposed compromises – a set of choices. If met, the demands would forever stave off rebellion. If refused, then war would prove inevitable.

Arkansas convened its Secession Convention on March 4, 1861, ironically, Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration day. Arkansas Governor Henry Rector bluntly declared the cause of discord: “They believe slavery is sin, and we do not, and there lies the trouble.” This rhetoric neatly comports with Lincoln’s December 1860 assessment to Alexander Stephens that “You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only substantial difference between us.”

Even with pro-slavery bombast dominating the convention, anti-secessionists held a majority for the moment. The two opinions, while increasingly difficult to hold simultaneously, were not yet inherently oppositional. With anti-secession prevailing, the convention adjourned on March 21. However, during the previous day, the majority made quite clear their opinion was contingent on a series of measures that would not only protect slavery, but ensconce white supremacy.

The Arkansas Resolutions blamed “The people of the northern States” for creating the Republican Party whose “central and controlling idea… is hostility to the institution of African slavery, as it exists in the Southern states,” while pledging “to administer the government upon principles inconsistent with the rights, and subversive of the interests of the people of the southern States.” Defending racialized slavery was clearly at the forefront of the convention’s collective mind.

The Arkansas Resolutions, 1861

“To redress the grievances” spelled out in the Resolutions’ opening, the convention proposed several amendments to the Constitution that would placate the slavery and race question forever.

First, the President and Vice President of the United States would alternately be chosen from a “slaveholding state and a non-slaveholding state,” but under no circumstances shall both offices be occupied simultaneously by persons both from a slave or non-slaveholding state.

Second, the Resolutions demanded that the Missouri Compromise line be reinstituted. In a gesture to anti-slavery Northerners, the amendment would forbid slavery in territory north of the line. However, “all the territory now held, or which may hereafter be acquired, south of said line of latitude, slavery of the African race is hereby recognized as existing, and shall not be interfered with by Congress….”

Despite acknowledging abolition in the Great Plains, this section was particularly filled with avarice. In the Western Hemisphere, slavery was only found in the southern United States, Cuba, and Brazil. Hence, any future acquisition of territory would in practice reinstitute slavery where abolition had already taken hold. The examples of Texas, David Walker’s filibuster in Nicaragua, and the Ostend Manifesto involving Cuba showed prominently that pro-slavery Americans had no compunctions of reverting free soil back into lands of bondage.[1]

Third, “Congress shall have no power to legislate upon the subject of slavery, except to protect the citizen in his right of property in slaves.” This demand was later fixed in the Confederate Constitution as Article 1, Section 9.4: “No bill of attainder… or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.”

The fourth and fifth proposed amendments aimed at strengthening the fugitive slave clause. Meanwhile the sixth proposed amendment in Arkansas’s Resolutions demanded federal protection of the right of slaveholders “traveling through, or temporarily sojourning with their slaves in non-slaveholding States” to retain their property rights despite what any free state wished to legislate on the subject.

Next was a convoluted amendment that would make amending these proposed amendments and the fugitive slave clause impossible without the consent of all the states of the Union.

Perhaps most odious of all these amendments was number seven. It bared naked the tyrannical soul of slavery and racism: “The elective franchise and the right to hold office, whether federal, State, territorial or municipal, shall not be exercised by persons of the African race, in whole or in part.”

To reiterate, absolutely all elective offices in the entire United States and the right to vote upon these offices would be denied to any person of African descent, “in whole or in part.” Assured these proposals would create a permanent racial caste system, Arkansas’s Resolutions concluded by blaming the “reckless and fanatical spirit of sectionalism north and south” for the impending civil war.

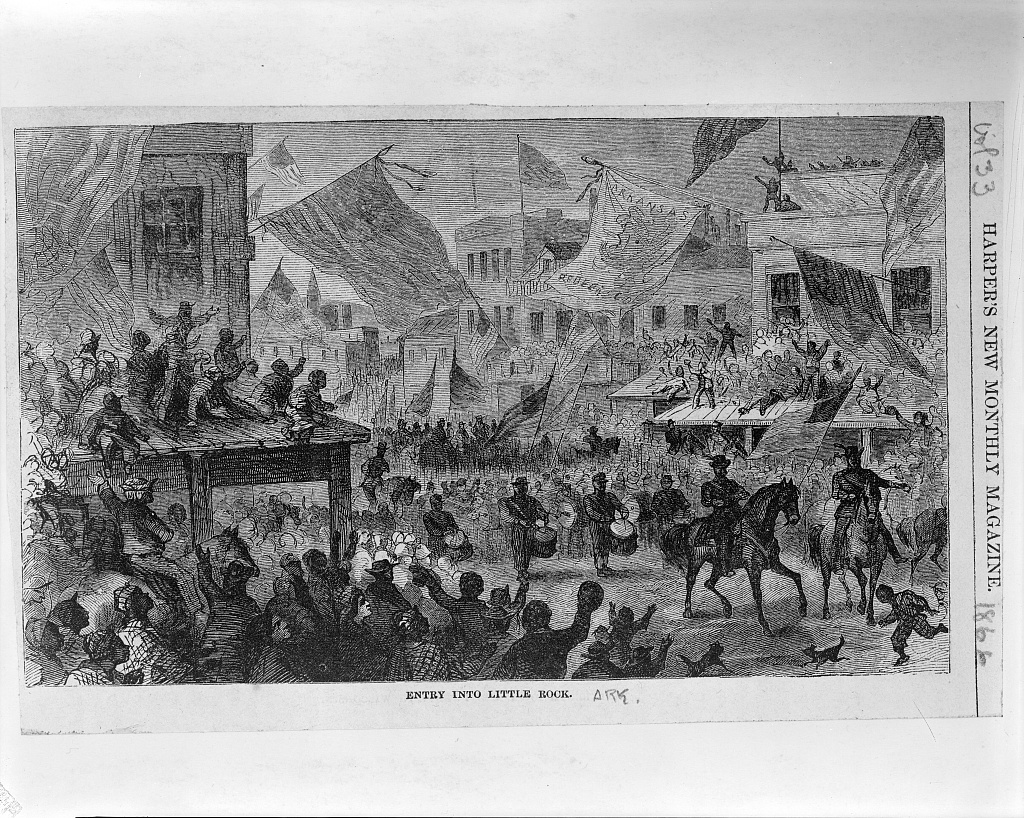

“Entry into Little Rock,” Harper’s Weekly, 1866

In their totality, these proposed amendments and so-called compromises forced free states to allow use of slave labor by slaveholders on free soil; instituted slavery on free soil acquired in the future by the United States; made the fugitive slave clause ironclad; forbade Congress from ever legislating upon slavery, unless it was strengthening the institution; and explicitly made politics the exclusive province of the white race.

Arkansas’s Resolutions were practically, if not ideologically, moot less than a month later when the Battle of Fort Sumter swung the tide toward secession in the state. Ultimately, all but one member (Isaac Murphy) of the reconvened Secession Convention voted to leave the United States.

INDIVIDUALS MAKE THEIR CHOICE

The Arkansas Resolutions’ idea of compromise, like the compromises our nation settled upon over the preceding century, was predicated on the economic exploitation and political exclusion of African Americans.

Mercifully, a sizable contingent of white Southerners found democracy better served in a Union without slavery than in disunion centered upon slavery. Their opinion on race and slavery should not be glossed over, however. In 1861 their views on the subject ranged from pro-slavery to ambivalence to anti-slavery. Nonetheless as the war progressed, their views hardened that Union, if not always complete racial equality, trumped slavery. Prominent Union generals like Winfield Scott and George H. Thomas, both of Virginia, chose country over state. To choose state over country, secession over Union, was to violate their oath to protect and defend the Constitution.

In 1862, the aforementioned Isaac Murphy joined the Union military in active opposition to the Confederacy. One of Murphy’s friends, James Johnson, organized the First Arkansas Infantry in 1863 from white Unionists in the state’s hilly northwest corner.

Even more strident in their defense of the Union were black Southerners hoping to speed up the nation’s new birth of freedom. Comprising 40{ec117f0059f8cde3a5e4f5b3c1b486659702d407977a37ffc575d2c0a9b4a69f} of the Confederacy’s population, enslaved blacks proved a powerful force in dismantling “state over country” sentiment and expanding democracy for all Americans. Nearly 95,000 black Southerners from the eleven rebellious states threw their lot in with the Union as soldiers and sailors. Nearly 40,000 more black men enlisted from the loyal slave states further eroded the cancerous spirit of slavery within the Union. From Arkansas, 5,500 black men were recruited into the armed services of the United States — an impressive number considering that there were 111,000 enslaved blacks in the state when the war began in 1861, including women, children, elderly men, and men physically unfit for service in the recruitment pool.

The Unionism of black and white Southerners, as well as that of white Northerners, did not always see eye-to-eye. Andrew Johnson of Tennessee denounced the Confederacy wholeheartedly and helped sweep aside slavery in his state during the war. As president however, Johnson believed emancipation from slavery was all the freedom that black Americans needed as he vetoed the 1866 Civil Rights Act. Meanwhile, black Unionists like South Carolinian Robert Smalls worked politically for decades after the war to establish and maintain civil rights and public education for all Southerners, regardless of race. As for white Northerners, the Compromise of 1877 that curtailed Reconstruction was a despondent return to “grand compromises” on race in the United States. And some former Confederates like James Longstreet and Amos Akerman, renounced the Confederate doctrine after the war and embraced Unionism. Longstreet was wounded while defending the biracial Louisiana state government against a riotous mob of white supremacists in 1874. Akerman would serve as Ulysses S. Grant’s Attorney General and personally led raids against the Ku Klux Klan in the early 1870s.

Despite the differences between the Unionists, to say nothing of their secessionists opponents, there was nonetheless a choice for all people to make. Complex choices, yes. But the choices were still marked clearly enough where all involved could demarcate the lines of Union and freedom versus disunion and the perpetuation of human bondage. The choice was particularly stark and obvious for men who took oaths to the defend the United States like Scott and Thomas, and even Robert E. Lee.

Lee was particularly free to choose his course of action. Lincoln offered him command of U.S. soldiers to fulfill his oath of duty, instead he chose to lead an army against the United States. Lee lived safely by the federal capital, yet chose to decamp for Richmond, whereas Southern Unionists far-removed from federal power when the war began formed Union regiments like the First Arkansas Infantry and the Second Arkansas Colored Infantry that fought against the Confederacy. Lee was relatively wealthy and could resist economic coercion from pro-secessionists, while many poor whites and enslaved blacks ran away to swamps, forests, and mountains in bids to resist the Confederacy until Union help arrived.

After the war, Lee again could have chosen a path that fully renounced the Confederacy and unbridled white supremacy like Akerman and Longstreet did. Lee did not.

We today, as always, have a set of grand issues to contend with. These issues may require reasonable compromise from all parties, but we should eschew political expedients built on the exploitation and degradation of others as our antebellum compromises were. President Lincoln was not perfect, as his acquiescence to the Corwin Amendment showed, but he made a determined point of referencing the aspirational words of the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal, and was repulsed by attempts to limit, rather than expand, those to whom that statement applied.

Fortunately, decision-making is a continuous process because new choices arise. Lincoln’s support for that first 13th Amendment yielded to evermore abolitionist measures concluding with the 13th Amendment now enshrined in our Constitution that abolished slavery.

Keeping the premise of human equality as his guiding philosophy, Lincoln defended the Emancipation Proclamation and the service of black Southerners, while chiding a segment of white Unionists, to say nothing of the recalcitrant Confederates, for their petulant racism that interfered with the Union: “there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they strove to hinder it.”

When it comes to the grand issues of every era, the people are aware of their choices, the possible compromises, and the stakes. Slavery and Union were the grand issues of 1861 and compromises were proposed. Options were on the table to consummate a victory for human liberty or ensure the triumph of slavery. Americans saw those options and made their choice.

Curtis Harris is a Museum Program Associate at President Lincoln’s Cottage, and a PhD History student at American University.

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

Arkansas Secession Convention. Resolutions Passed by the Convention of the People of Arkansas. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/media-detail.aspx?mediaID=7352

Central Arkansas Library System. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/

Constitution of the Confederate States of America. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_csa.asp

William C. Davis. Look Away!: A History of the Confederate States of America.

David C. Downing. A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy.

Matthew Karp. This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy.

Abraham Lincoln. Letter to James Conkling. http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/conkling.htm

James Madison. Notes on the Debates in the Federal Convention. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/debcont.asp

Stephanie McCurry. Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South.

Andrew Ward. The Slaves’ War: The Civil War in the Words of Former Slaves.

[1] For more on the efforts of pro-slavery Americans to internationally expand slavery and reopen the international slave trade, see Matthew Karp’s This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy.